Training for Bloodborne Pathogens: Everything You Need to Know

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) published the Occupational Exposure to Bloodborne Pathogens standard in 1991. Here’s everything you need to know about bloodborne pathogen training.

Germs are a part of our everyday life. While most of them are helpful, some can cause illness, organ and tissue damage, or disease.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality reports that less than 1 percent of bacteria actually make people sick. Yet that small percentage of pathogens can mean the difference between life and death.

Many of us know how important it is to wash our hands and cover our mouths when we sneeze and cough. Practicing good hand hygiene prevents the spreading of these infectious agents. But, some pathogens spread through different forms of transmission like from needle sticks or other sharps.

Nearly two-thirds of nurses report that they have been stuck by a needle while working. These injuries hold a high risk of spreading bloodborne pathogens.

Due to the risks associated with bloodborne pathogen exposure, the government had to step in. Thus, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) published the Occupational Exposure to Bloodborne Pathogens standard in 1991.

A large part of that standard focuses on the requirement associated with bloodborne pathogen training.

Although the standard lays out specific topics that bloodborne pathogen training should include, it’s not an easy read.

Thus, bringing us to this blog post. Here’s everything you need to know about bloodborne pathogen training.

What is a Bloodborne Pathogen?

So what are bloodborne pathogens and how can we protect ourselves from them?

To put it simply, they’re infectious microorganisms in our blood that can cause disease.

Some examples include hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Workers in different occupations may be at risk for exposure such as…

- First responders

- Housekeeping personnel

- Nurses

- Other healthcare professionals

The risk of transmission of bloodborne infections does depend on the pathogen and the volume and type of blood exposure. For example, some pathogens can still spread in the absence of visible blood contamination. Whereas diseases such as malaria need large volumes of blood to spread, like from a blood transfusion.

Exposure to these pathogens may occur in many ways, but needlestick injuries are by far the most common cause. Approximately 600,000 to 800,000 needlestick occurs among healthcare workers annually.

Another CDC study reports that sharp-tip suture needles are the leading source of these injuries, causing about 51% to 77% of incidents.

Exposure may also occur through contact with contaminants with the nose, mouth, eyes, or skin. Luckily, there are standard precautions in place to help reduce the chance of spreading infection thanks to OSHA and the CDC.

OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Standard

OSHA's Bloodborne Pathogens Standard provides safeguards to protect employees against bloodborne pathogen transmission. Thus, if you are in an occupation in which you may deal with blood, body fluids, or tissues, this standard, and its requirements, apply to you.

To reduce exposure to bloodborne pathogens, an employer must install an exposure control plan. This plan should be subject to review annually to update to new procedures and technological advancements.

It also includes...

- Engineering controls

- Work practice controls

- Guidelines on personal protective equipment (PPE)

Engineering and work practice controls are the primary methods to reduce exposure to bloodborne pathogens.

Engineering controls aim to stop the hazard at the source before it comes in contact with the worker. When engineering controls are not available, work practice controls are the next defense.

Work practice controls are behavior-based habits. These include recapping needles before disposal and disposing of sharps immediately after use.

If engineering and work practice controls don’t eliminate exposure, make sure to use PPE for any remaining risk.

Engineering Controls

Engineering controls are the first line of defense when reducing the risk of spreading bloodborne diseases.

Examples include…

- Self-sheathing needles

- Safety sharps

- Sharps disposal containers

- Needle recapping devices

- Blunt-tip suture needles

- Needleless IV ports

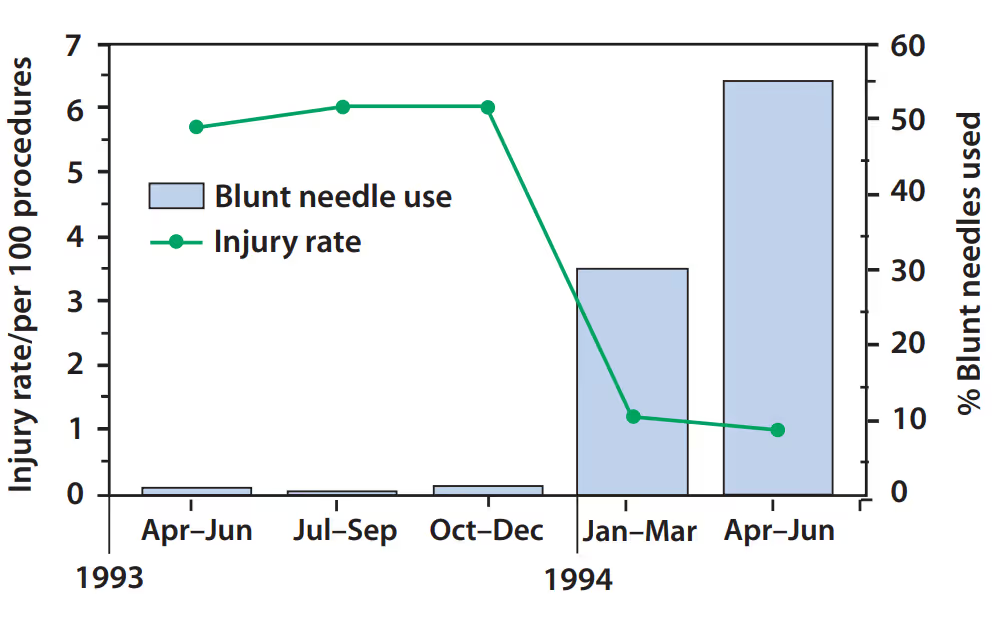

The replacement of sharp-tip suture needles with blunt-tip greatly reduces the risk of sharps injuries in a surgical environment.

These suture needle injuries can occur when surgical personnel…

- Load or reposition the needle into the needle holder.

- Pass the needle hand-to-hand to a team member.

- Sew toward another team member while they hold back tissue.

- Leave the needle on the operative field.

- Place needles in an overfilled sharps container.

The CDC study also showed how blunt-tip sutures effectively act as an engineering control. Blunt-tip sutures are often used to suture less-dense tissue like muscle and fascia. As many as 59% of suture needle injuries occur during the repair of these tissues. The study found a significant reduction in injury rates in comparison to using sharp-tip.

Work Practice Controls

When talking about the next safeguard, it’s important to remember that it isn’t about what you use but how you use it.

Work practice controls have less to do with the devices that are available and more to do with altering mannerisms while performing a task. For instance, if a needle-recapping device is not available, a one-handed "scoop" technique can recap a needle if necessary. This involves using the needle itself to pick up the cap and pushing the cap and sharp together against a hard surface to ensure a tight fit.

A few other work practice controls aren’t bending, shearing, or breaking of used needles. Also, make sure to…

- Enforce hand washing procedures

- Restrict eating and drinking in work areas

- Decontaminate equipment

Making sure to not use the same syringe or needle for multiple patients or use a contaminated syringe to draw medication is an important workplace practice control. Whenever possible, using single-dose vials over multiple-dose can help eliminate the likelihood of cross-contamination between patients.

According to the CDC, a survey of US healthcare workers who provide medication through injection found that 1% to 3% reused the same needle and/or syringe on multiple patients. This is a prime way of transmission of bloodborne diseases.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Finally, we have the use of personal protective equipment (PPE).

PPE refers to wearable equipment that cuts exposure to hazardous and infectious materials. This equipment acts as a barrier for your skin, mouth, nose, or eyes whenever there is possible exposure to infectious material.

Remember, this is not your first line of defense! Instead, this protection supplements the engineering control and work practice control safeguards.

PPE can block the transmission of contaminants from blood, body fluids, or respiratory secretions.

Some examples of PPE include…

- Gloves

- Face masks

- Protective eyewear

- Face shields

- Protective clothing like disposable gowns or coats

While wearing PPE, it’s important to keep your hands away from your face, limit the surfaces you touch, and remove them when leaving a work area. The sequence for removing PPE is to remove gloves first, then goggles, gown, and lastly mask. Hand sanitizing should always be the final step after having disposed of the used PPE.

Conclusion

Exposure control plans must contain…

- Engineering controls

- Work practice controls

- Personal protective equipment (PPE)

However, each of these control types breaks into further specific procedures. Cleaning and disinfection of equipment, handling laundry, post-exposure follow-up, and so on all play a role.

Complying with the OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Standard protects employers from lawsuits. This, of course, also protects employees and patients from injury and exposure to disease.

Knowing how to protect yourself and prevent exposure to bloodborne pathogens can make a difference in your community. Yet all the equipment and information will do you no good if you’re not taking annual training.

Putting that knowledge into practice regularly can help you prevent an accident which is better - and simpler than a cure.

Emphasize your product's unique features or benefits to differentiate it from competitors

In nec dictum adipiscing pharetra enim etiam scelerisque dolor purus ipsum egestas cursus vulputate arcu egestas ut eu sed mollis consectetur mattis pharetra curabitur et maecenas in mattis fames consectetur ipsum quis risus mauris aliquam ornare nisl purus at ipsum nulla accumsan consectetur vestibulum suspendisse aliquam condimentum scelerisque lacinia pellentesque vestibulum condimentum turpis ligula pharetra dictum sapien facilisis sapien at sagittis et cursus congue.

- Pharetra curabitur et maecenas in mattis fames consectetur ipsum quis risus.

- Justo urna nisi auctor consequat consectetur dolor lectus blandit.

- Eget egestas volutpat lacinia vestibulum vitae mattis hendrerit.

- Ornare elit odio tellus orci bibendum dictum id sem congue enim amet diam.

Incorporate statistics or specific numbers to highlight the effectiveness or popularity of your offering

Convallis pellentesque ullamcorper sapien sed tristique fermentum proin amet quam tincidunt feugiat vitae neque quisque odio ut pellentesque ac mauris eget lectus. Pretium arcu turpis lacus sapien sit at eu sapien duis magna nunc nibh nam non ut nibh ultrices ultrices elementum egestas enim nisl sed cursus pellentesque sit dignissim enim euismod sit et convallis sed pelis viverra quam at nisl sit pharetra enim nisl nec vestibulum posuere in volutpat sed blandit neque risus.

Use time-sensitive language to encourage immediate action, such as "Limited Time Offer

Feugiat vitae neque quisque odio ut pellentesque ac mauris eget lectus. Pretium arcu turpis lacus sapien sit at eu sapien duis magna nunc nibh nam non ut nibh ultrices ultrices elementum egestas enim nisl sed cursus pellentesque sit dignissim enim euismod sit et convallis sed pelis viverra quam at nisl sit pharetra enim nisl nec vestibulum posuere in volutpat sed blandit neque risus.

- Pharetra curabitur et maecenas in mattis fames consectetur ipsum quis risus.

- Justo urna nisi auctor consequat consectetur dolor lectus blandit.

- Eget egestas volutpat lacinia vestibulum vitae mattis hendrerit.

- Ornare elit odio tellus orci bibendum dictum id sem congue enim amet diam.

Address customer pain points directly by showing how your product solves their problems

Feugiat vitae neque quisque odio ut pellentesque ac mauris eget lectus. Pretium arcu turpis lacus sapien sit at eu sapien duis magna nunc nibh nam non ut nibh ultrices ultrices elementum egestas enim nisl sed cursus pellentesque sit dignissim enim euismod sit et convallis sed pelis viverra quam at nisl sit pharetra enim nisl nec vestibulum posuere in volutpat sed blandit neque risus.

Vel etiam vel amet aenean eget in habitasse nunc duis tellus sem turpis risus aliquam ac volutpat tellus eu faucibus ullamcorper.

Tailor titles to your ideal customer segment using phrases like "Designed for Busy Professionals

Sed pretium id nibh id sit felis vitae volutpat volutpat adipiscing at sodales neque lectus mi phasellus commodo at elit suspendisse ornare faucibus lectus purus viverra in nec aliquet commodo et sed sed nisi tempor mi pellentesque arcu viverra pretium duis enim vulputate dignissim etiam ultrices vitae neque urna proin nibh diam turpis augue lacus.