CMMC SSP: What It Is and Why You Need One

Here is everything you need to know about a CMMC SSP and why you need to have one if you work within the space.

This technical guide was reviewed by the CMMC 2.0 specialist team at K2 GRC. Expert Reviewer: Todd Stanton

Effective system security planning improves the protection of information systems. NIST SP 800-171 defines 110 security requirements to protect Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI). One of the compliance requirements includes developing a system security plan (SSP). A SSP outlines the controls in place or planned for meeting security requirements. Such as those regarding access control, system integrity, and incident response. SSPs also describe the components within the system and the environment of operation. An SSP must also describe the components within the system and the environment of operation.

The purpose of this blog is to:

- Identify when you need a SSP

- Justify components of a SSP

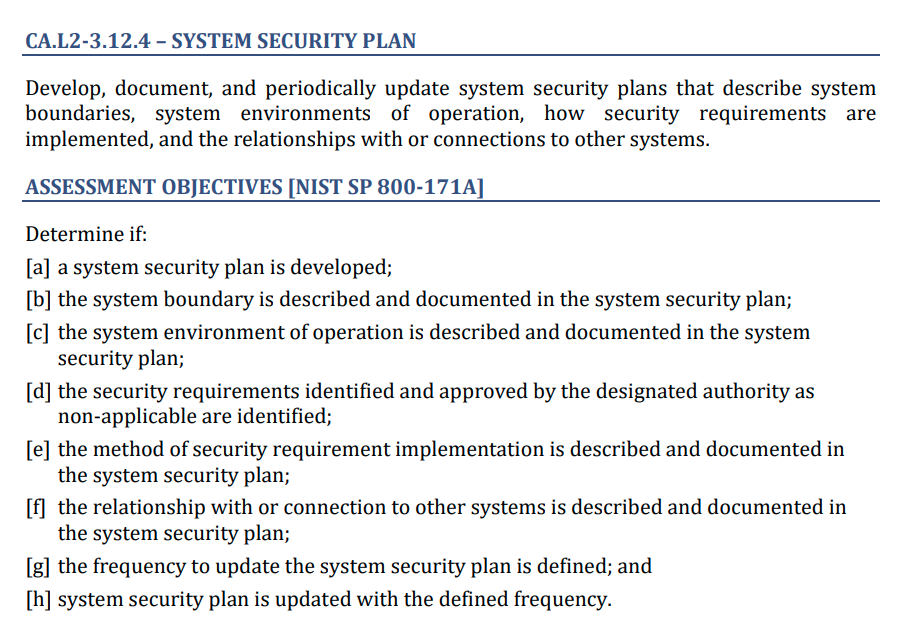

- Address objectives a through h of CA.L2-3.12.4

- Link to Government SSP Templates

- Explore automation for SSP generation

When Do You need an SSP?

The US Government imposed 15 cybersecurity requirements for federal contractors in 2016. The Department of Defense (DoD), NASA, and the GSA published 52.204-21 in the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR). The regulation applied to "covered contractor information systems" handling Federal Contract Information (FCI). Having a system security plan is not required to meet these requirements.

NIST developed SP 800-171 as the standard for safeguarding CUI in nonfederal systems. The 2016 revision specified new requirements for documenting and developing an SSP. A new FAR rule may include CUI safeguarding practices for all federal agencies. Some agencies, including DoD, have already adopted its use for nonfederal partners. DoD applied these requirements to contractors handling Covered Defense Information in 2016.

In 2020, DoD published interim rule 252.204-7019. This requires organizations to submit a self-assessment score of their SP 800-171 implementation. This only applies to organizations handling CUI on nonfederal systems. To submit the basic assessment score, contractors must submit the name of their robust reviewing a Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC) System Security Plan SSP. Contractors were not required to submit their SSP as part of their self-assessment. The 7019 clause required contractors to update self assessment affirmations every three years.

At the same time, DoD published interim rule 252.204-7020. This clause enables the Government to conduct their own assessments of contractors. A medium assurance assessment involves a review of the contractor's SSP. A high assurance assessment involves a demonstration of their SSP. DoD may request a contractor's SSP as part of a medium or high-assurance assessment. DoD expected 444 medium and 243 high assurance assessments in the first three years.

In 2025, CMMC will enhance DoD's verification of these existing cybersecurity regulations. CMMC Level 1 allows for continued self-attestations to the FAR basic safeguarding requirements. Contractors handling FCI still do not need a system security plan. CMMC Level 2 introduces third-party assessments to verify NIST 800-171 R2 implementations. Most contractors and subcontractors handling CUI will need a third-party assessment. Failing a CMMC certification assessment may prevent contractors from working on future contracts.

The CMMC Assessment Process (CAP) lists reviewing reviewing a CMMC SSP as the first step in a Level 2 assessment. Assessors will first examine the document for completeness, accuracy, and consistency. This review should provide the assessor a reasonable expectation you met the requirements. Further assessment activities will check the adequacy and sufficiency of your implementation.

If you're a party to DoD contracts and handling CUI, you need to create an SSP. If you're only handling FCI and not CUI, you don't need a SSP.

Key Components of a System Security Plan

NIST SP 800-18 describes the development of an information system security plan. You can tailor this guidance down to the objectives detailed in 3.12.4 within NIST SP 800-171A.

These objectives became the basis for Practice CA.L2-3.12.4 within CMMC v2.13. Let’s start with the specific requirements for a SSP related to achieving CMMC compliance. We’ll use NIST SP 800-18, the CAP, and NIST SP 800-171A Rev 3 for supplemental guidance.

(A) How to Create an SSP Templates for CMMC Compliance?

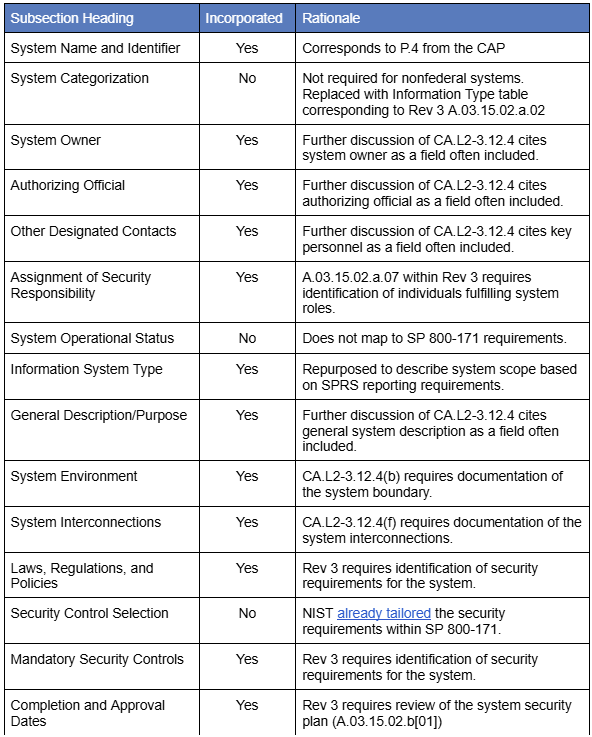

Section 3 of NIST SP 800-18 discusses plan development. Here are the subsection headings from SP 800-18. We included our rationale for incorporating them into the SSP template:

We compared the SP 800-18 guidance with CMMC requirements. This included a review of the certified CMMC final rule, the CMMC Level 2 Assessment Guide and Scoping Guide. We also reviewed the updated CMMC Assessment Process (CAP). Consideration was also made for guidance from the Supplier Performance Risk System (SPRS). After this review, we settled on the following SSP must have headings:

Organization

This table identifies the name, address, and phone number of the organization. A DUNS number field satisfies step P.3 from the CAP. A Cage Code(s) field satisfies the CMMC requirements identified in §170.18(a)(1)(I)(C). The Cage Code(s) field satisfies step P.4 of the CAP. This section also helps establish the initial roles and responsibilities for the system's ownership.

Document Revision History

This table tracks major and minor updates made to the system security plan. Tracking updates documents compliance with CA.L2-3.12.4(h). The version field satisfies requirements identified in §170.18(a)(1)(i)(D). The date field tracks the date of major or minor updates. A description field allows for a brief narrative of the changes made. The author field identifies the individual responsible for the changes.

Authorization

This table captures the contact information for the authorization official. This is a senior management official who has the authority to accredit the system. Contact information includes the name, title, address, email address, and phone number. A signature field captures the authorization of the SSP. Capturing the signature satisfies requirements identified in §170.24(b)(1). The date field captures when the authorization occurred.

System Scope

The system scope table categorizes the scope according to the SPRS portal:

- Enterprise. An information security system with a defined boundary used to execute an organization's mission. The organization has the responsibility for managing its own risks and performance.

- Enclave. A set of system resources operating in the same security domain. These resources share the protection of a single, common, continuous security perimeter.

General System Description

This section should describe the function and purpose of the system. This narrative should be between one and three paragraphs.

System Components

These tables identify components within the system boundary. System components include technology, facilities, and types of users. There is no requirement to embed every asset in the organization’s SSP. We included system component tables to address asset categorization.

The facilities table identifies the facility name and address. Organizations should populate this table with facilities that provide security protection to CUI.

The second table identifies the types of users associated with the system. Fields include roles, privileges, and functions performed.

The technology table identifies the types of systems present. Technology fields include component name, category, and type. The type identifies the functionality of the asset. The category value identifies the categorization according to the CMMC Scoping Guide. Identification of CMMC Scope meets requirements described in §170.19(c). These tables facilitate step 1.2 from the CAP and help describe the system boundary [CA.L2-3.12.4(b)].

Network Diagram

Including a network diagram provides evidence for CA.L2-3.12.4(b). A graphical depiction of the system boundary also helps meet SC.L2-3.13.1(a). If the depiction includes key internal system boundaries, it can help meet SC.L2-3.13.1(b).

Facility Diagrams

Facility diagrams define protected physical spaces within facilities. These diagrams address scoping discussions related to step 1.3 of the CAP.

Information Types

NIST SP 800-60 assigns responsibility for identifying information types to the system owner. The system owner may delegate this responsibility to designees. This includes any information stored in, processed by, or generated by the system. Each type of information identified should have a supporting description. We included this section based on A.03.15.02.a.02 within SP 800-171A Rev 3.

Data Flow Diagram

Providing a data flow diagram addresses section §170.19(c) and supports step 1.3 from the CAP. The assessment guide lists data flow diagrams as a common type of evidence examined. The assessment guide includes several references to data flow with SC.L2-3.13.1. We have written more information on how to create a data flow diagram here.

Threats of Concern

This section allows for a brief description of specific threats to the system. These threats should only include those of concern to the organization. We included this section based on A.03.15.02.a.04 within SP 800-171A Rev 3. Identification of specific threats is also the first step towards meeting AT.L2-3.2.1(a). Identification of security risks starts with identifying specific threats. Risk assessments also include considerations of likelihood and impact. Properly identifying these risks helps to shape an effective incident response plan.

System Environment of Operation

This section allows for a brief description of the technical system. The inclusion of this section maps to CA.L2-3.12.4(c). It also helps meet part of A.03.15.02.a.04 within SP 800-171A Rev 3.

System Interconnections

NIST SP 800-47 defines system interconnections. These are direct connections between two or more systems in different authorization boundaries. The inclusion of this section maps to CA.L2-3.12.4(f). Documenting interconnections helps meet AC.L2-3.1.20(a). It also helps meet the second part of A.03.15.02.a.04 within SP 800-171A Rev 3.

Information System Owner

The system owner coordinates system development life cycle activities. The assessment guide suggests organizations identify the system owner within the SSP. This person should have expert knowledge of the system capabilities and functionality. Document the same contact information as described in the authorization official table.

Other Designated Contacts

These tables identify other key contact personnel. The assessment guide suggests that organizations identify the key personnel within the SSP. These individuals can address inquiries about system characteristics and operation. Document the same contact information as described in the authorization official table.

Mandatory Security Controls

This table incorporates the 110 practices within CMMC Level 2. Incorporating this table addresses A.03.15.02.a.05 within SP 800-171A Rev 3. The first column includes the NIST identification number for all requirements. The second column identifies a description of each control. The third column identifies the practice number from the assessment guide.

Control Originations

Organizations may inherit implementations from an external service provider (ESP). Organizations should document the use of an ESP within their SSP. This table establishes definitions for one of three potential implementation methods:

- Internal. Describes controls developed and implemented by the organization responsible for the information system.

- Shared. Describes a control that has some functions provided by ESP. The organization responsible for the system provides some responsibilities on shared controls.

- Inherited. Describes controls developed, implemented, assessed, authorized, and monitored by an ESP.

Implementation

The rest of the template describes the organization's implementation of security requirements. The requirements appear in the same order as presented in the assessment guide. Domain headings separate the 14 control families. All requirements include a number and name. Below each number and name is the practice statement.

Below the practice statement is a control summary table. Organizations should identify responsible individuals to address step 2.6 of the CAP. It also helps meet A.03.15.02.a.07 within SP 800-171A Rev 3.

The control summary table also includes fields for the status of security requirements. Organizations should self-assess their implementation of each practice using the assessment objectives. The control summary implementation status combines the status of the relevant objectives. Implementation statuses may include:

- Met

- Partial

- Not Met

- Not Applicable

The last field within the summary table identifies the origination of the implementation. This field maps back to one of three values from the Control Originations table.

Below the control summary table are the determination statements. The tables list each determination statement from the assessment guide. Next to each is a field to identify the implementation status. Below each is a table with a column for scope and implementation statement(s). Describing the method of implementation for requirements meets CA.L2-3.12.4(e). Ensure that your implementation descriptions reference the specific security policies that govern them. This links your SSP to broader governance documentation.

(B) Describe and document the system boundary

The sections of the SSP that describe and document the system boundary include:

- System Scope

- General System Description

- System Components

- Network Diagram(s)

- Facility Diagram(s)

The System Scope table categorizes the system as either an enclave or enterprise. This categorization describes the protection boundary for CUI. Partitioning information systems into enclaves may reduce the resources required to secure systems.

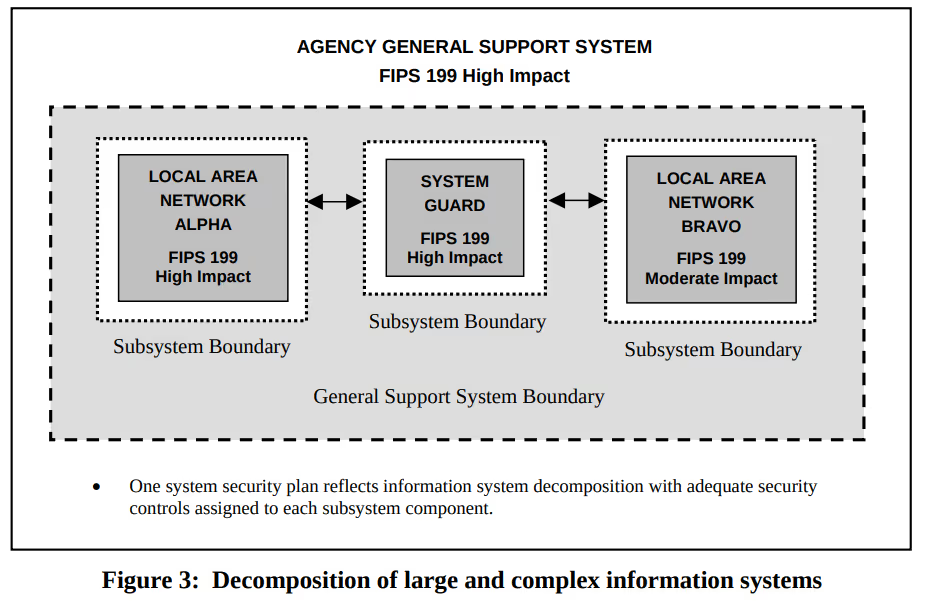

NIST SP 800-18 uses similar terms, such as general support system and subsystems. Section 2.3 discusses general support systems. These are a set of interconnected information resources that share common functionality. General support systems may include hardware, software, data, applications, communications, facilities, and people. They may provide support for a variety of users and/or applications.

It is possible for an information system to contain one or more subsystems. A subsystem is a major component consisting of information, technology, and personnel. Figure 3 depicts a general support (enterprise) system with three subsystems (enclaves).

The General System Description describes the function and purpose of the system. Enterprise systems will likely have a broader function and purpose than enclaves. Enclaves may perform one or more specific functions.

The System Components tables define the constituent system components. Section 2.1 of NIST SP 800-18 discusses system boundaries. Assigning information resources to a system defines the security boundary for that system. Organizations have flexibility in determining what makes up an information system. NIST identifies three points to consider when including components into a system boundary:

- Subsystems are under the same management authority.

- Information resources have similar operating characteristics and security needs.

- Information resources operate within the same general operating environment. In distributed systems, information resources should operate within similar operating environments.

Section 2.2 discusses major applications. These are systems that perform functions with identifiable security considerations and needs. Major applications may comprise many programs, hardware, software and telecommunications components.

Section 2.4 discusses minor applications. General support systems or major applications may provide security controls to minor applications. The organization should document security controls specific to minor applications in the SSP. Minor applications may operate on systems without adequate boundary protection. In this case, all baseline controls become applicable to minor applications.

A network diagram is a visual representation of the components within a system. Read more about creating network diagrams here. Network diagrams should include:

- CUI Assets

- Security Protection Assets

- Contractor Risk Managed Assets

- Specialized Assets

- External boundary

- Internal boundaries

A facility diagram should define the protected physical spaces of facilities. This includes environments (rooms, offices, etc.) containing sensitive information. Each facility should have a diagram categorizing public and non-public areas. Read more about creating facility diagrams here.

(C) Describe and document the system environment of operation

The system environment of operation description should be between one and three paragraphs. Include any environmental or technical factors that raise special security concerns. This may include the use of mobile devices or wireless technology. NIST SP 800-70 provides four categories of nonfederal system environments:

- Standalone. The Standalone environment consists of devices managed as separate units.

- Managed. Managed environments provide administrators centralized control over various device settings. This includes administration of authentication, account, and policy management functions.

- Specialized Security-Limited Functionality (SSLF). The SSLF describes systems that have the higher threats and associated impacts. Security takes precedence over functionality within SSLF systems. An SSLF environment could be a subset of another environment or self-contained environments.

- Legacy Environments. A Legacy environment contains older systems or applications. They often use older, less secure communication mechanisms. Systems in a Legacy environment may need less restrictive security settings to communicate. Legacy environments are often subsets of other environments.

(d) Identify the non-applicable security requirements

There may be security requirements or attributes that aren't applicable to your organization. Question 63 from the DFARS FAQ and §170.24(c)(2)(B)(i)( 8) discuss this scenario. A contractor may provide a written explanation to their contracting officer. The explanation may detail the reasons for non-applicability. It may also detail how alternatives are as effective. The contracting officer will refer the proposed variance to the DoD CIO. The time-frame for adjudication should occur within five business days.

Question 65 addresses an alternative. Organization policies or processes may not allow circumstances addressed by NIST SP 800-171. In these instances, the organizational practices may meet the requirements. For example:

- AC.L2-3.1.12. Organizations that prevent remote access may consider this an implementation of the requirements.

- AC.L2-3.1.18. Organizations that disallow mobile device connections meet the requirements.

If the organization prohibits the functionality, you may consider the requirements implemented. Marking requirements as not applicable requires DoD adjudication. Organizations must include DoD adjudications within their SSP.

(E) Describe and document the method of implementation for each security requirement

The implementation section describes the method of implementation for all requirements. For each met control, NIST SP 800-18 instructs the description to contain:

- The security control title

- Implementation of the security control

- The FedRAMP Training - How to Write a Control provides the following tips:

- Use consistent terminology throughout the SSP

- Be direct and to the point

- Run grammar/spell check

- Every control part (a, b, c) should contain a focused discussion

- Avoid restating requirements when describing implementations

- Do not copy and paste boilerplate text over and over again

- Do not include text not relevant to describing the implementation

- Do not leave control implementation descriptions blank

- Use the verbs in the control to explain the implementation

- As appropriate, consider who, what, when, where, why, and how for each control element

- Reference policies and procedures by title, data and version

- An overview of referenced documents should rely the implementation

- Include a table at the end of the SSP that specifies referenced documents

- Include Applicable scoping guidance or considerations

- The FedRAMP Training - How to Write a Control provides the following tips:

- The inventory may include more than one platform

- Address unique implementations of the same requirements

- Controls from AC, IA, AU, CM, and SI may vary by platform

- Use a standard format for addressing controls by platform

- Where applicable, address each facility including alternate facilities

- The inventory may include more than one platform

- Identify if the security control is a common control

- Identify the individual responsible for its implementation

(f) Describe and document the relationship with or connection to other systems

The system interconnections table identifies relations with or connections to other systems. Interconnections may exchange information and/or allow access to information, services, and resources. NIST SP 800-18 and the FedRAMP Moderate SSP Template provide guidance on this table. Organizations may tailor the headings of this table to their own needs. The headings we included in the template include:

- External system name

- Connection Security

- This may include IPSec, VPN, SSL, Certificates, Secure File Transfer, etc.

- Data Direction

- This may include incoming, outgoing, or both

- Information transmitted

- This should map back to information types

- Communication method

- Identify ports and protocols used

Other headings we’ve seen incorporated into this table include:

- System Component

- Identifies the internal network connection point

- External Organization

- External IP Address

- External Point of Contact and Phone Number

- Purpose of the interconnection

(g) Define the frequency to update the SSP

Our crosswalk of NIST SP 800-171 Rev 2 relates CA.L2-3.12.4 to PL-2 from NIST SP 800-53. PL-2 has a FedRAMP defined organization defined parameter for PL-02 ODP[03]. This requires SSP updates to occur at least once a year. Organizations should also update the SSP whenever significant changes occur.

(h) Update the SSP with the defined frequency

Whenever updating the SSP, the owner should:

- Add a version number

- Document the date the authorizing official approved the plan

- Attach the approval documentation (accreditation letter, approval memorandum)

Government SSP Templates

NIST and FedRAMP each provide their own SSP templates. The links below will allow you to download any of the templates we used when we created our own template.

- NIST SP 800-171 Template. This template outlines the recommended security requirements for protecting the confidentiality of CUI in nonfederal systems.

- NIST SP 800-18 Template. This template is available as PDF within Appendix A of SP 800-18. It incorporates many of the required section headings. Keep in mind that some of the headings are only relevant to federal systems. Since it is a PDF, it is not practical to use a template.

- NIST CUI-SSP Template. This word template incorporates many of the required sections. It does not incorporate a table to identify system interconnections. It does not include details around the assessment objectives.

- FedRAMP SSP Moderate Baseline Template. This word template includes more section headings than required. It does go down to the assessment objectives, but it includes the SP 800-53 Moderate controls. It does not account for variances in control implementations by platforms.

Automating your SSP Generation

GRC platforms may enable organizations to export a SSP. The degrees of detail contained within these templates varies. If you considering using a platform to build your SSP, consider the following:

- Does the SSP contain all relevant sections required by CMMC?

- Does the SSP address all control objectives?

- Does the SSP address implementation variations by platform?

If you haven’t found one that checks these three boxes, watch our brief virtual demonstration.

Emphasize your product's unique features or benefits to differentiate it from competitors

In nec dictum adipiscing pharetra enim etiam scelerisque dolor purus ipsum egestas cursus vulputate arcu egestas ut eu sed mollis consectetur mattis pharetra curabitur et maecenas in mattis fames consectetur ipsum quis risus mauris aliquam ornare nisl purus at ipsum nulla accumsan consectetur vestibulum suspendisse aliquam condimentum scelerisque lacinia pellentesque vestibulum condimentum turpis ligula pharetra dictum sapien facilisis sapien at sagittis et cursus congue.

- Pharetra curabitur et maecenas in mattis fames consectetur ipsum quis risus.

- Justo urna nisi auctor consequat consectetur dolor lectus blandit.

- Eget egestas volutpat lacinia vestibulum vitae mattis hendrerit.

- Ornare elit odio tellus orci bibendum dictum id sem congue enim amet diam.

Incorporate statistics or specific numbers to highlight the effectiveness or popularity of your offering

Convallis pellentesque ullamcorper sapien sed tristique fermentum proin amet quam tincidunt feugiat vitae neque quisque odio ut pellentesque ac mauris eget lectus. Pretium arcu turpis lacus sapien sit at eu sapien duis magna nunc nibh nam non ut nibh ultrices ultrices elementum egestas enim nisl sed cursus pellentesque sit dignissim enim euismod sit et convallis sed pelis viverra quam at nisl sit pharetra enim nisl nec vestibulum posuere in volutpat sed blandit neque risus.

Use time-sensitive language to encourage immediate action, such as "Limited Time Offer

Feugiat vitae neque quisque odio ut pellentesque ac mauris eget lectus. Pretium arcu turpis lacus sapien sit at eu sapien duis magna nunc nibh nam non ut nibh ultrices ultrices elementum egestas enim nisl sed cursus pellentesque sit dignissim enim euismod sit et convallis sed pelis viverra quam at nisl sit pharetra enim nisl nec vestibulum posuere in volutpat sed blandit neque risus.

- Pharetra curabitur et maecenas in mattis fames consectetur ipsum quis risus.

- Justo urna nisi auctor consequat consectetur dolor lectus blandit.

- Eget egestas volutpat lacinia vestibulum vitae mattis hendrerit.

- Ornare elit odio tellus orci bibendum dictum id sem congue enim amet diam.

Address customer pain points directly by showing how your product solves their problems

Feugiat vitae neque quisque odio ut pellentesque ac mauris eget lectus. Pretium arcu turpis lacus sapien sit at eu sapien duis magna nunc nibh nam non ut nibh ultrices ultrices elementum egestas enim nisl sed cursus pellentesque sit dignissim enim euismod sit et convallis sed pelis viverra quam at nisl sit pharetra enim nisl nec vestibulum posuere in volutpat sed blandit neque risus.

Vel etiam vel amet aenean eget in habitasse nunc duis tellus sem turpis risus aliquam ac volutpat tellus eu faucibus ullamcorper.

Tailor titles to your ideal customer segment using phrases like "Designed for Busy Professionals

Sed pretium id nibh id sit felis vitae volutpat volutpat adipiscing at sodales neque lectus mi phasellus commodo at elit suspendisse ornare faucibus lectus purus viverra in nec aliquet commodo et sed sed nisi tempor mi pellentesque arcu viverra pretium duis enim vulputate dignissim etiam ultrices vitae neque urna proin nibh diam turpis augue lacus.