CyberAB July Town Hall: 6 Key Takeaways

The newly rebranded CyberAB held their monthly virtual Town Hall meeting on July 26, 2022. During the event came the release of the much anticipated CMMC Assessment Process (CAP). Here are 6 main key takeaways from the event.

The newly rebranded CyberAB held their monthly virtual Town Hall meeting on July 26, 2022. During the event came the release of the much anticipated CMMC Assessment Process (CAP).

We’ve written a separate summary of this draft publication to assist those looking to understand what it says.

We’ll focus this update on what else they discussed. We'll also provide some commentary on recent announcements made by the Department of Defense (DoD) and the Department of Justice (DoJ)..

Here are our key takeaways for the July Town Hall and recent DoD/DoJ/NIST Announcements…

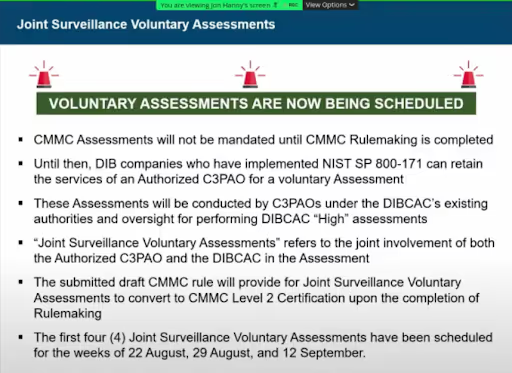

Voluntary Assessments Started

With the Version 1.0 draft of the CMMC Assessment Process published, the Cyber AB and accredited CMMC 3rd Party Assessment Organizations (C3PAOs) are moving forward with the voluntary assessment program

The CyberAB coined the phrase "Joint Surveillance" during the townhall. It now describes the pre-rulemaking process. This process includes oversight from the Defense Industrial Base Cybersecurity Assessment Center (DIBCAC).

According to the AB, there are four voluntary assessments already scheduled with the earliest beginning on August 22, 2022.

The program will rely on the 166 Provisional Assessors (PAs) listed on the marketplace. The CyberAB hasn’t certified any Certified Assessors (CAs) or Certified CMMC Professionals (CCPs).

The AB expects these voluntary assessments will convert to Level 2 Certifications eventually. This of course only happens if there aren't any significant changes to the program as drafted in CMMC 2.0.

Image Source: The Cyber AB

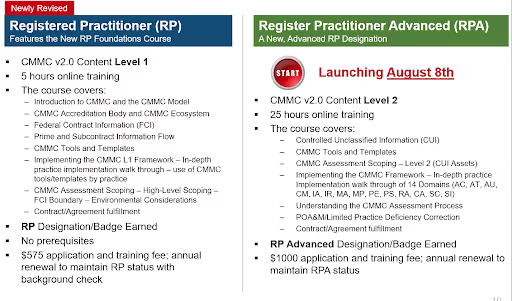

CyberAB - Registered Practitioner Advanced (RPA)

The announcement of the new Advanced Registered Practitioner badge ruffled a lot of feathers. Specifically in the consultant, assessor and training silos of the ecosystem.

The CyberAB has always advocated for two paths for individuals performing services in the ecosystem. One for consultants and one for assessors.

To be a Registered Practitioner (RP) today, an individual must pay $575, undergo a background check and pass a series of quizzes following 5 hours of online training.

There was no required background knowledge of cybersecurity required to pass the quizzes and there was no training on how to implement NIST SP 800-171 controls.

There are individuals who want to learn how assessors will evaluate the implementation of these controls. This includes both consultants and assessors. Many of them have already registered for and taken the Certified CMMC Professional (CCP) training.

These courses, provided by Licensed Training Providers (LTPs) , started at the end of 2021. The classes were typically one week of virtual or in-person instruction at a cost of around $2k to $4k per person.

Early birds who took the training still have to wait until October 2022 to take the exam before they can receive the CCP credentials.

But now the CyberAB has introduced a path that would steer consultants away from CCP by offering Registered Practitioner Advanced (RPA) training. It builds on the prerequisite Registered Practitioner foundation.

This track would be about half the cost up front compared to CCP training but the annual renewal fee is 4x higher ($250 for CCP vs $1,000 for RPA).

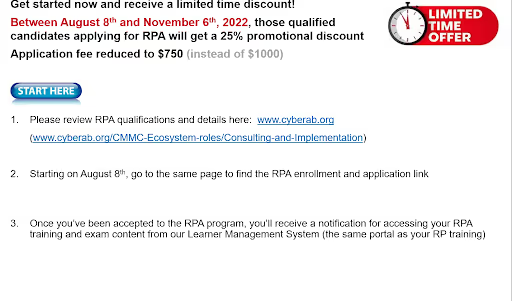

The Cyber AB announced a limited time offer for a reduced application fee ($750 instead of $1,000) but noted that RPA applicants must also meet additional experience requirements and respond to questions on prior assessing experience as part of the application process.

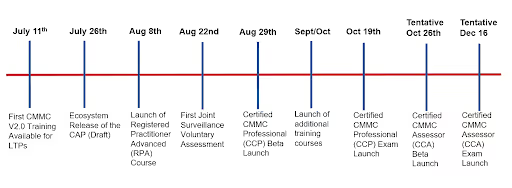

2022 Second Half Momentum

Much of the July meeting focused on updates related to the upcoming exam dates for CMMC Certified Professionals and Assessors. The Cyber AB provided a summary slide showing the flurry of upcoming milestones they plan on achieving or have achieved in the second half of 2022.

DoD - Memo on Non-Compliance

In March, the Defense Industrial Base Cybersecurity Assessment Center (DIBCAC) announced they were planning on starting medium assurance assessments in the coming months.

On June 16, 2022, John Tenaglia, the Principal Director of Defense Pricing and Contracting, published a memo reminding contracting officers of the means available to them to ensure contractor compliance with NIST SP 800-171.

- DFARS clause 252.204-7020 which states:

- “(c) Requirements. The Contractor shall provide access to its facilities, systems, and personnel necessary for the Government to conduct a Medium or High NIST SP 800–171 DoD Assessment, as described in NIST SP 800–171 DoD Assessment Methodology at Strategically Assessing Contractor Implementation of NIST SP 800-171, if necessary.”

A Medium Assessment consists of:

- A review of the contractor’s self assessment of NIST SP 800-171

- A thorough document review (of the System Security Plan)

- Discussions with the contractor to obtain additional information

A High Assessment consists of:

- A review of the contractor’s self assessment of NIST SP 800-171

- A thorough document review (of the System Security Plan)

- Verification, examination, and demonstration of a Contractor’s system security plan to validate the implementation of NIST SP 800-171 security requirements

- Discussions with the contractor to obtain additional information

In short, when a contracting officer initiates a medium or high assessment, DIBCAC will request a copy of the contractor’s System Security Plan (SSP) and they expect to receive it within 5 business days.

In the last 30 days, we can confirm that DIBCAC has started conducting Medium Assessments and they are only allowing 120 days for remediation of controls self-assessed as met but identified as insufficient by their Medium Assessment.

DoD considers failure to make progress on a plan to implement NIST SP 800-171 requirements as a “material breach” of contract requirements and this memo lists remedies for such a breach as:

- Withholding progress payments

- Foregoing remaining contract options

- Terminating the contract in part or in whole

The memo reminds its readers that the 252.204-7020 clause took effect on November 30, 2020 through DFARS interim rule 2019-D041. The 7020 clause should be present in all subsequent solicitations, contracts, task orders, or delivery orders since, except for those dealing with the acquisition of commercial off the shelf products. Contracts, task orders etc. issued prior to November 30, 2020 would not contain this clause and the memo suggests two alternative methods to enforce compliance.

2. In the event the contractor does not have the DFARS clause 252.204-7020 in their current contract, the memo advises contracting officers to negotiate bilateral modifications to incorporate the clause.

3. If the contractor does not have the DFARS clause 252.204-7020 and the contracting officer does not have the ability to negotiate its incorporation, the memo advises contracting officers to verify the contractor has self assessment loaded into the Supplier Performance Risk System (SPRS) prior to exercising any new option, extension, modification, task order, or delivery order.

This requirement comes from DFARS procedure 204.7303 that also took effect on November 30, 2020, through DFARS interim rule 2019-D041. The updated procedure reads as follows:

(b) The contracting officer shall verify that the contractor has posted a summary level score of their current NIST SP 800–171 DoD Assessment (i.e., not more than 3 years old) (see 252.204–7019) in the Supplier Performance Risk System (SPRS) (https:// www.sprs.csd.disa.mil/) for each covered information system that is relevant to an offer, contract, task order, or delivery order prior to—

(1) Awarding a contract, task order, or delivery order to an offeror or contractor that requires implementation of NIST SP 800–171 in accordance with the clause at 252.204–7012; or

(2) Exercising an option period or extending the period of performance on a contract, task order, or delivery order with a contractor that requires implementation the NIST SP 800–171 in accordance with the clause at 252.204–7012.

Although DIBCAC will not conduct Medium or High Assessments without the DFARS 252.204-7020 provision, companies knowingly misrepresenting their cybersecurity practices or protocols, as memorialized in their SPRS self-assessment, risk facing a False Claims Act and substantial civil penalties.

DOJ - AeroJet RocketDyne False Claims Act Settlement

It’s astonishing that a 21st century aerospace company with revenues in the billions of dollars had to settle a civil case based on a law that dates back to 1863. Congress enacted the False Claims Act in response to defense contractor fraud during the American Civil War. More than a century and a half later, the DoJ has a renewed focus on pursuing companies who receive federal funds and fail to implement required cybersecurity standards.

The government doesn’t need to initiate a False Claims Act and as in the case of AeroJet RocketDyne (AR), they weren’t even a party in the case.

Whistleblowers, known as qui tam relators, can file complaints and receive between 15% and 30% of the fine if a judge or jury finds the contractor violated the act. Fines can be up to three times the value of the contract plus over $11,000 per claim.

The AR case is an important precedent for False Claims Act cases related to cybersecurity requirements amongst DoD contractors and suppliers. Although it was only settled very recently, the case actually predates DoD contract requirements to implement NIST SP 800-171.

The whistleblower filed their first complaint on October 29, 2015. The current NIST SP 800-171 requirements did not become a requirement under DFARS 252.204-7012 until December 31, 2017.

However, DoD has required contractors to implement safeguarding cybersecurity practices identified in DFARS Case 2011-D039 since November 18, 2013.

AR employed the relator as the senior director for Cyber Security, Compliance & Controls from June 2014 to September 2015. The relator alleged that AR fraudulently induced the government to contract with them knowing that they were not complying with the required cybersecurity practices.

The scope of the lawsuit included six contracts that contained the DFARS or NASA FAR clauses awarded between February 2014 and October 2015.

The judge ruled that a seventh contract, which included DD Form 254 which required AR to comply with, “all laws and regulations governing access to Unclassified Controlled Technical Information” would remain in scope as well.

The relator filed two claims of fraud against AR…

- 31 USC 3729(a)(1)(A) - knowingly presents a false or fraudulent claim for payment or approval

- 31 USC 3729(a)(1)(B) - knowingly makes or uses a false record or statement material to a false or fraudulent claim

To prove the first claim of false certification, the Supreme Court ruled in June 2016 that…

“the implied false certification theory can be a basis for FCA liability when a defendant submitting a claim makes specific representations about the goods or services provided, but fails to disclose noncompliance with material statutory, regulatory, or contractual requirements that make those representations misleading with respect to those goods or services.” (via Universal Health Services, Inc. v. United States Ex Rel. Escobar)

To prove the second claim of promissory fraud, the US District Court for DC ruled that

“to prevail under a fraudulent inducement theory, the plaintiff must prove that the omitted information was material and that it induced the government, who relied on the fraudulent statement or omission when it awarded the contract” (via Thomas v. Siemens AG, 991 F. Supp. 2d 540, 569 (E.D. Pa. 2014))

Here is what the relator alleged in their claim:

- AR hired an outside firm to investigate a data breach in 2013. The relator produced a memo generated by this outside firm that outlined four incidents that occurred which resulted in large quantities of data leaving the AR network.

- AR hired an outside firm in 2014 to assess the required DFARS 252.204-7012 controls. The relator produced an audit report conducted that showed they were only compliant with 5 of the 59 required controls under DFARS 252.204-7012.

- From 2013 to 2015, AR employed an outside firm to conduct penetration testing of their network. The relator produced audits showing the outside firm was able to penetrate AR’s network within four hours.

Request for Summary Judgment and Ruling

A summary judgment is a judgment entered by a court for one party against the other without a full trial. In the AR case, the relator requested a summary judgment for their first claim of false certification and AR requested a summary judgment for both claims.

The court based the summary ruling on an evaluation of these essential elements of liability:

- a false statement or fraudulent course of conduct

The court granted AR’s motion for summary judgment on the false certification claim because the claim relied on an invoice payment for a contract entered after the relator had filed their complaint.

The court denied the relator’s motion for a summary judgment on the promissory fraud claim because AR had disclosed noncompliance with the at issue regulations to the contracting agencies.

The court granted AR’s motion for summary judgment on the promissory fraud claim if they could show the absence of material fact and one or more of the three elements of promissory fraud.

- made with Sienter (knowingly or reckless disregard of the truth)

The court denied AR’s motion for summary judgment on the promissory fraud claim because the relator’s evidence showed AR knew they needed to comply with the DFARS and NASA FAR clauses and were aware of their noncompliance through outside audits.

- that was material (capable of influencing the government),

The court found the disclosures that AR provided to the contracting agencies were insufficient and therefore could not grant a summary judgment on the promissory fraud claim based on the materiality element.

- causing the government to pay out money or forfeit moneys due

Since the court found the disclosures insufficient, they concluded it was reasonable that the government might not have contracted with AR had it known what the relator argues AR should have told them. The court therefore denied AR a summary judgment on the promissory fraud claim based on the causation element.

Since AR failed to show the absence of material fact on one or more of the three remaining elements of promissory fraud, the court considered a summary judgment of damages. The relator requested the maximum damages at three times the value of the seven contracts, totaling over $19 billion. Conversely, AR contended there were no damages and the government received full economic value of the goods and services provided.

The court concluded they could not adjudicate through a summary judgment as no precedent supported either proposition. On April 26, 2022, the case opened in a jury trial with the relator seeking a minimum of $2.6 billion in damages. The very next day, AR agreed to settle the case for $9 million, of which the relator will receive $2.1 million.

NIST - Open to Public Comments for SP 800-171 Updates

On July 19, 2022, NIST issued a call for public comments to solicit feedback from stakeholders seeking to improve the Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI) series of publications. NIST will start with Special Publication 800-171 which was first introduced in 2015 and last updated in February of 2020. NIST is also seeking feedback on the supporting publications SP 800-171A, SP 800-172 and SP 800-172A.

NIST acknowledges that since February 2020, there have been significant changes in cybersecurity threats, vulnerabilities, capabilities, technologies, and resources that impact the protection of CUI. NIST is seeking feedback on the use, effectiveness, adequacy and ongoing improvement of the CUI series. They suggested relevant topics for comments:

- How are organizations currently using the CUI series

- How are they using it with other frameworks and standards (CSF)

- How to improve alignment with other frameworks and standards

- Benefits and challenges of the CUI series

- Impacts of Rev 5 of SP 800-53 on backward compatibility

- Requests to change, add or remove features

- The potential inclusion of NFO controls

The comment period is open through September 16, 2022 using the email address 800-171cmments@list.nist.gov.

Emphasize your product's unique features or benefits to differentiate it from competitors

In nec dictum adipiscing pharetra enim etiam scelerisque dolor purus ipsum egestas cursus vulputate arcu egestas ut eu sed mollis consectetur mattis pharetra curabitur et maecenas in mattis fames consectetur ipsum quis risus mauris aliquam ornare nisl purus at ipsum nulla accumsan consectetur vestibulum suspendisse aliquam condimentum scelerisque lacinia pellentesque vestibulum condimentum turpis ligula pharetra dictum sapien facilisis sapien at sagittis et cursus congue.

- Pharetra curabitur et maecenas in mattis fames consectetur ipsum quis risus.

- Justo urna nisi auctor consequat consectetur dolor lectus blandit.

- Eget egestas volutpat lacinia vestibulum vitae mattis hendrerit.

- Ornare elit odio tellus orci bibendum dictum id sem congue enim amet diam.

Incorporate statistics or specific numbers to highlight the effectiveness or popularity of your offering

Convallis pellentesque ullamcorper sapien sed tristique fermentum proin amet quam tincidunt feugiat vitae neque quisque odio ut pellentesque ac mauris eget lectus. Pretium arcu turpis lacus sapien sit at eu sapien duis magna nunc nibh nam non ut nibh ultrices ultrices elementum egestas enim nisl sed cursus pellentesque sit dignissim enim euismod sit et convallis sed pelis viverra quam at nisl sit pharetra enim nisl nec vestibulum posuere in volutpat sed blandit neque risus.

Use time-sensitive language to encourage immediate action, such as "Limited Time Offer

Feugiat vitae neque quisque odio ut pellentesque ac mauris eget lectus. Pretium arcu turpis lacus sapien sit at eu sapien duis magna nunc nibh nam non ut nibh ultrices ultrices elementum egestas enim nisl sed cursus pellentesque sit dignissim enim euismod sit et convallis sed pelis viverra quam at nisl sit pharetra enim nisl nec vestibulum posuere in volutpat sed blandit neque risus.

- Pharetra curabitur et maecenas in mattis fames consectetur ipsum quis risus.

- Justo urna nisi auctor consequat consectetur dolor lectus blandit.

- Eget egestas volutpat lacinia vestibulum vitae mattis hendrerit.

- Ornare elit odio tellus orci bibendum dictum id sem congue enim amet diam.

Address customer pain points directly by showing how your product solves their problems

Feugiat vitae neque quisque odio ut pellentesque ac mauris eget lectus. Pretium arcu turpis lacus sapien sit at eu sapien duis magna nunc nibh nam non ut nibh ultrices ultrices elementum egestas enim nisl sed cursus pellentesque sit dignissim enim euismod sit et convallis sed pelis viverra quam at nisl sit pharetra enim nisl nec vestibulum posuere in volutpat sed blandit neque risus.

Vel etiam vel amet aenean eget in habitasse nunc duis tellus sem turpis risus aliquam ac volutpat tellus eu faucibus ullamcorper.

Tailor titles to your ideal customer segment using phrases like "Designed for Busy Professionals

Sed pretium id nibh id sit felis vitae volutpat volutpat adipiscing at sodales neque lectus mi phasellus commodo at elit suspendisse ornare faucibus lectus purus viverra in nec aliquet commodo et sed sed nisi tempor mi pellentesque arcu viverra pretium duis enim vulputate dignissim etiam ultrices vitae neque urna proin nibh diam turpis augue lacus.