CMMC Level 1 Continuous Monitoring: Everything You Need to Know

Here’s everything you need to know about CMMC Level 1 continuous monitoring.

This blog discusses strategies for monitoring the effectiveness of security requirements. Control assessments are infrequent, often occurring only once per year. Continuous monitoring activities can provide better awareness of threats, vulnerabilities, and control effectiveness.

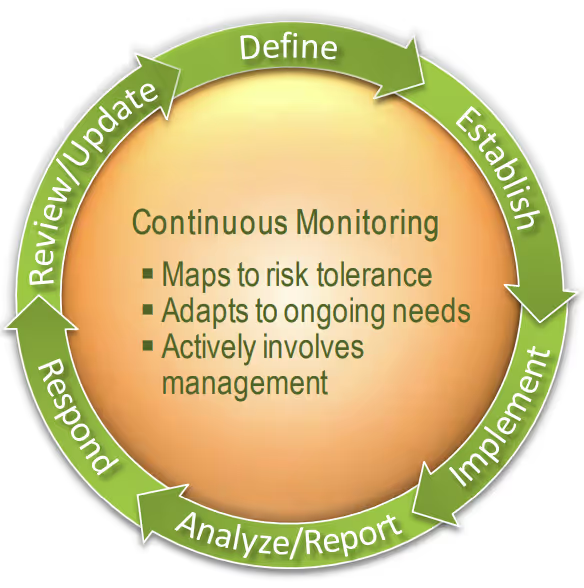

NIST SP 800-137 defines the information security continuous monitoring (ISCM) process:

- Defining an ISCM program

- Establishing an ISCM program

- Implementing an ISCM program

- Analyzing data and Reporting findings

- Responding to findings; and

- Reviewing and Updating the ISCM strategy

The purpose of this post is to define an ISCM for CMMC Level 1 security requirements.

Update System Maintenance Log

There are four types of records to update or review within a system maintenance log on a weekly basis. This includes:

- Update Electronic Media Records

- Review and Analyze Audit Records

- Review Exceptions to Maintenance Plans

- Review Antivirus Software Updates

Update Electronic Media Records

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-88. Organizations should track media sanitization efforts. Maintain records when introducing, moving, or sanitizing media. Record keeping helps track sanitization for all media introduced into the operating environment. Update maintenance records when the media reaches the sanitization destination. Documentation details may depend on the confidentiality level of the media. When required, complete a certificate of media disposition for sanitized electronic media. This may include either an electronic or paper record of the action taken. For convenience, a Fillable Certificate of Sanitization template is available courtesy of PeakInfoSec.

Updating media records evidence for the following CMMC Level 1 objectives:

- MP.L1-b.1.vii (a) sanitize or destroy system media containing [FCI] before disposal

- MP.L1-b.1.vii (b) sanitize media containing [FCI] before release for reuse

Evidence:

- Media sanitization records

Policy Statement:

Media Protection

- We sanitize media with sensitive information before releasing it outside the organization. We verify sanitization results and document each action taken. Sanitization also applies when reusing media in systems with a lower impact level. We remove identifying markings when reusing media in lower impact systems. We verify the destruction of all hard copy media disposed of in shred bins.

Review and Analyze Audit Records

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-61. Organizations should establish procedures to ensure adequate collection and review of log information. This may be tedious if filtering is not used to condense the logs to a reasonable size. Handlers should focus on unexplained entries, which are usually more important to investigate. Conducting frequent log reviews enables identification of trends and changes over time. The reviews also reveal the reliability of each source.

Reviewing audit records establishes evidence for the following CMMC Level 1 objectives:

- SC.L1-b.1.x (c) monitoring communications at the external system boundary

- SC.L1-b.1.x (d) monitoring communications at key internal system boundaries

Evidence:

- System audit logs and records

Policy Statements:

System and Information Integrity

- We analyze log data in real-time to detect unusual or suspicious activity. We maintain a baseline of device access and internal network services. We use the baseline to identify anomalies and respond to emerging threats.

Review Exceptions to Maintenance Plans

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-40. Organizations should track all exceptions to maintenance plans. Define maintenance groups to reduce assets considered “exceptions.” Having some exceptions is inevitable. Review all exceptions and determine whether you can use the maintenance plan now. Move assets with similar long-term exceptions to a separate maintenance group.

Reviewing maintenance plan exceptions establishes evidence for the following CMMC Level 1 objectives:

- SI.L1-b.1.xii (f) correct system flaws within the specified time frame

Evidence:

- Test results from the installation of software and firmware updates

Policy Statements:

Maintenance

- Maintenance group definitions identify outage restrictions, impact levels, and existing mitigations.

- Every asset has an assigned maintenance group. For each group, we identify relevant software to maintain patching.

System and Information Integrity

- We deploy vendor-supplied security patches within six months of their release. We deploy critical patches within two weeks of their release.

- We review exceptions to the maintenance plan every week.

Verify Antivirus Software Updates

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-83. Organizations should centralize management of antivirus software. Assign responsibilities for acquiring, testing, approving, and delivering antivirus signatures and updates. Prevent users from disabling or deleting antivirus software or altering critical settings. Administrators should confirm that hosts are using current antivirus software with correct configurations . Implementing these recommendations supports a strong and consistent antivirus deployment across the organization.

Updating antivirus establishes evidence for the following CMMC Level 1 objectives:

- SI.L1-b.1.xiii (b) provide protection from malicious code at designated locations

- SI.L1-b.1.xiv (a) update malicious code protection when releases are available

Evidence:

- Records of malicious code protection updates

Policy Statements:

System and Information Integrity

- We configure antivirus software to install updates and scan systems weekly.

Review of Account Access

This guidance originates from AC-2 within NIST SP 800-53. Identification of authorized users and privileges reflect the requirements in other controls. Users requiring administrative privileges on system accounts should receive extra scrutiny. Control AC-2 has a FedRAMP Moderate assigned parameter that states:

- Review accounts for compliance with account management requirements:

quarterly for privileged access, and once a year for non-privileged access.

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-12. From time to time, it is necessary to review user account management on a system. Within the area of user access, reviews may examine:

- the levels of access each individual has

- conformity with the concept of least privilege

- whether all accounts are still active

- whether management authorizations are up-to-date

- completion of required training

Organizations may conduct these reviews on applications or system-wide. Organizations may use in-house systems personnel, internal audit staff, or external auditors. It is a good practice for application managers to review user access levels every month. Signing an access approval list provides a written record of the approvals. Conducting reviews by systems personnel is usually less effective. System personnel can verify that users only have accesses specified by their managers. Since access requirements may change, it is important to involve the application manager. They often best understand current access requirements.

Documenting reviews establishes evidence for the following CMMC Level 1 objectives:

- AC.L1-b.1.i (a) identify authorized users

- AC.L1-b.1.i (b) identify processes acting on behalf of authorized users

- AC.L1-b.1.i (d) limit system access to authorized users

- AC.L1-b.1.i (e) limit system access to processes acting on behalf of authorized users

- AC.L1-b.1.ii (b) limit system access to transactions and functions defined for authorized users.

Evidence:

- list of active system accounts and the names of the associated individuals

- notifications or records of recently transferred, separated, or terminated employees

- list of recently disabled system accounts along with the names of associated individuals

- access authorization records

- system audit logs and records

- list of approved authorizations including remote access authorizations

Policy Statement:

Account Management

- We document all authorized user credentialing activities. We maintain accurate records of authorized users from on-boarding to termination. Job requirements determine access to systems, data, and non-public spaces.

- We maintain a list of authorized processes, documenting who granted permission for each.

- We revoke system access when employees leave the organization.

- We disable accounts that have been inactive for 30 days.

Update System Component Inventory

This guidance originates fromNIST SP 800-137. Accurate system component inventories improve the effectiveness of patch management and vulnerability management. Control CM-8 from NIST SP 800-53 has a FedRAMP Moderate assigned parameter that states:

- Review and update the system component inventory at least monthly or when there is a change.

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-128. ThA process of discovery populates the component inventory. Discovery is the process of obtaining system component information that composes the systems. Discovery processes may be manual or automated. The organization determines the types and granularity of the components in the inventory. Automated tools are generally a more effective means of maintaining component inventories. Even with automated tools, it may be necessary to enter some component inventory data. Examples include unique identifiers, system associations, owner, administrator, user, or type of component. Inventory management tools are usually database-driven applications that track and manage system components. Automated tools may detect the removal or addition of components. Some tools allow for expanded monitoring of components. With this functionality, organizations can track changes in the component’s configuration.

Component inventories can help track approved configuration baselines, configuration changes, and security impacts. Some data elements stored for each component in the system inventory include:

- Unique Identifier and/or Serial Number

- System that includes this component

- Type of component

- Manufacturer/Model information

- Operating System Type

- Version/Service Pack Level

- Presence of virtual machines

- Application Software Version

- License information

- Physical location

- Logical location (e.g., IP address)

- Media Access Control (MAC) address

- Owner

- Operational status

- Primary and secondary administrators

- Primary user (if applicable).

Other data elements may include:

- Status of the component

- Relationships to other components

- Dependencies on other systems

- Supported systems

- Service-Level Agreements (SLA)

- Common secure configurations

- Controls supported by this component

- Incident logs that apply

Documenting reviews establishes evidence for the following CMMC Level 1 objectives:

- AC.L1-b.1.i (c) identify devices (and other systems) authorized to connect to the system

- AC.L1-b.1.i (f) limit system access to authorized devices (including other systems)

- IA.L1-b.1.v (c) identify devices accessing the system

Evidence:

- list of devices and systems authorized to connect to organizational systems

Policy Statement:

Configuration Management

- We maintain an up-to-date inventory of system components reflecting the current system. The inventory includes firmware, operating systems, configuration baselines and associated applications and ports.

Review Physical Access Logs

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-53. Reviewing physical access logs helps identify suspicious activity, anomalous events, or potential threats. Automated system access logs can support the reviews.

Control PE-6 from NIST SP 800-53 has a FedRAMP Moderate assigned parameter that states:

- Review physical access logs at least monthly and upon defined events.

Control PE-8 from NIST SP 800-53 has two FedRAMP Moderate assigned parameters:

- Maintain visitor access records to the facility where the system resides for at least (1) year.

- Review visitor access records at least monthly

Access record reviews determine if authorizations are current and support business functions. Access records are not required for areas accessible to the public. Visitor access records should include the following details:

- Names and organizations

- Visitor signatures

- Forms of identification

- Dates of access

- Entry and departure times

- Purpose of visits

- Names and organizations of individuals visited

Reviewing physical access logs establish evidence for the following CMMC Level 1 objectives:

- PE.L1-b.1.ix (c) - maintain audit logs of physical access

Evidence:

- Physical access control logs or records

Policy Statement:

Physical and Environmental Protection

- We maintain detailed audit logs that track individuals accessing non-public spaces.

Check for and Report on New Vulnerabilities

This tasks consists of two related activities:

- Identifying system flaws

- Reporting system flaws

Identifying system flaws

NIST SP 800-160 defines a flaw as an imperfection or defect.

This guidance originates from the discussion of SI-2 within NIST SP 800-53. The need to remediate system flaws applies to all types of software and firmware. Organizations identify systems affected by flaws and report this information to designated personnel. Flaw discovery comes from assessments, continuous monitoring, incident response activities, and error handling.

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-40. Know when new software vulnerabilities affect applications, operating systems, and firmware. This involves knowing assets in use and which software those assets run. Subscribe to vendor vulnerability feeds, security researchers, and the National Vulnerability Database (NVD).

NIST SP 800-160 defines a vulnerability as an exploitable weakness.

Vulnerability monitoring and scanning (RA-5) is a related control to SI-2. Control RA-5 from NIST SP 800-53 has a FedRAMP Moderate assigned parameter that states:

- Check and scan for vulnerabilities monthly and after identifying potential vulnerabilities.

Reporting system flaws

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-40. Plan the risk response. This involves assessing the risk the vulnerability poses to your organization. Choose which form(s) of risk response to use, and decide how to put the risk response in place. Elevated risks may include vulnerabilities exploited in the wild and present in assets. You may choose to mitigate the risk by upgrading software or altering its settings.

Examples of common steps for preparing to deploy a patch include the following:

- Prioritizing the patch. A higher priority patch may reduce cybersecurity risk more than other patches would. A lower priority patch may only address lower-risk vulnerabilities.

- Scheduling patch deployment. Many organizations schedule patch deployments as part of their enterprise change management activities.

- Acquiring the patch. You may download a patch, have a developer build it, or receive it through removable media.

- Validating the patch. Confirm the patch’s authenticity and integrity before testing or installing the patch.

- Testing the patch. Testing a patch reduces risk by identifying problems before placing it into production.

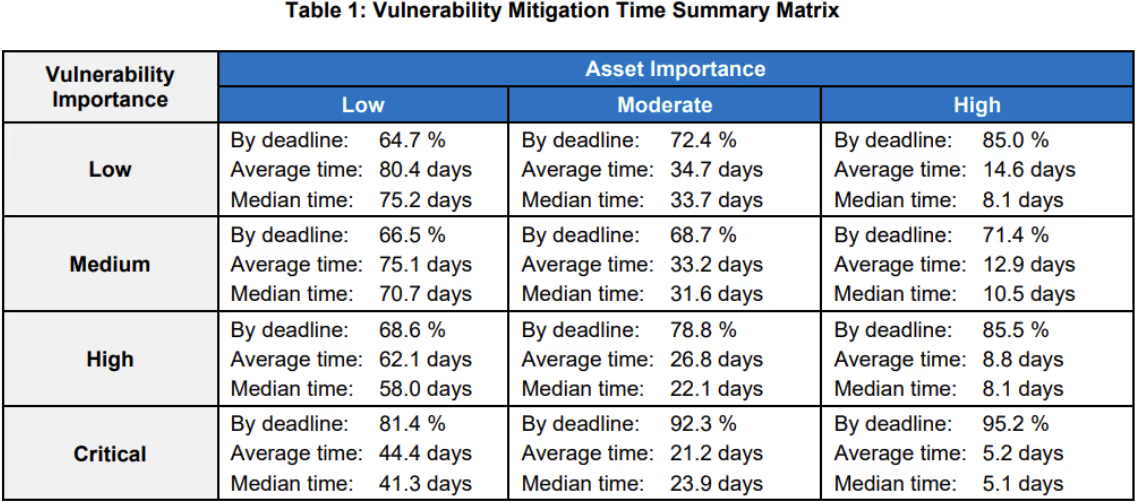

Take advantage of low-level metrics already collected when developing enterprise-level performance metrics. There is often information already available from software and asset inventories. This may include assets’ technical and mission/business characteristics. Organizations often have detailed information about the vulnerabilities. This includes CVSS scores, threat intelligence, and metrics provided by vulnerability management tools. This information helps identify the importance of each mitigated vulnerability.

Develop enterprise-level metrics that reflect the relative importance of each vulnerability and patch. Simplistic metrics, such as quantity and patch percentages, are not actionable. Reporting that 10 % of your assets were not patched does that measure risk. What is the relative importance of each of those assets? If they are the most important assets, then not patching them might be a major problem. If they are less important, not patching them indicates prioritization of resources. Report at assets based on the relative severity of the vulnerabilities.

Simple metrics are not actionable because they do not provide enough information. They do not offer the insights into the performance of vulnerability management. They do not identify improvements that could improve vulnerability management performance. Table 1 shows a notional example of actionable performance metrics. Each cell provides metrics based on asset importance and vulnerability severity. The metrics identify the percentage of assets patched based on the maintenance plan. It also reports the average and median time for patching.

You can also analyze mitigation data by platform, business unit, or other characteristics. This may help identify deficiencies or set targets for improving performance. It can also provide relevant metrics to executives, operations staff, and compliance professionals.

Set a schedule to update low-level metrics and strive for them to be as accurate as possible. Incorrect low-level metrics will impact the enterprise-level metrics calculated from them. Scanning for vulnerabilities monthly might make the number of vulnerabilities identified seem small. This would provide a misleading picture of the organization’s vulnerability management program. Only running unauthenticated vulnerability scans will also under-report vulnerabilities and skew the metrics.

Checking for new vulnerabilities establishes evidence for the following CMMC Level 1 objectives:

- SI.L1-b.1.xii (b) - identify system flaws within the specified time frame

- SI.L1-b.1.xii (d) - report system flaws within the specified time frame

Evidence:

- List of flaws and vulnerabilities that might affect the system

- Test results from software and firmware updates to correct system flaws

Policy Statement:

System and Information Integrity

- We maintain a database of identified vulnerabilities. We schedule planned remediations based on exploitation likelihood and impact. We review security alerts from US-CERT, CISA, and vendors every week. We conduct scans for software and firmware vulnerabilities every month.

Patching and Risk Response Verification

This guidance originates from the discussion of SI-2 within NIST SP 800-53. Time periods for updating security-relevant software and firmware vary based on risk factors. Factors include the system's security category, vulnerability severity, risk tolerance, and threat environment. Some types of flaw remediation may need more testing than other types. Determine the type of testing needed and the changes that are configuration-managed. You may determine testing updates is not necessary or practical. For example, when implementing simple malicious code signature updates. Consider whether you are obtaining updates from authorized sources with appropriate digital signatures.

Control SI-2 from NIST SP 800-53 has a FedRAMP Moderate assigned parameter that states:

- Install security-relevant software and firmware updates within thirty (30) days of release.

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-40. At a high level, examples of common steps for deploying a patch include the following:

- Distributing the patch. Distribute the patch to the assets that need to have it installed. This may include organization-controlled or vendor-controlled assets.

- Validating the patch. Confirm the patch’s authenticity and integrity before testing or installing the patch.

- Installing the patch. Installation can occur through automated or manual means. Some installations may need administrator privileges or involve user participation.

- Changing software configuration and state. In some cases, making a patch take effect necessitates implementing changes. Examples include altering configuration settings, restarting, rebooting, redeploying the application or system.

- Resolve any issues. Installing a patch may cause side effects. This may include altering existing security configuration settings or adding new settings. These side effects can create a new security problem while fixing the original one. Correcting issues may involve uninstalling the patch or reverting to a previous version. In some cases, you may need to restore the asset or software from backups.

Verifying a patch’s deployment can ensure successful installation. The robustness of verification is dependent on an organization’s needs. Automated means are generally needed to achieve verification at scale.

Monitoring the patch’s deployment using automation confirms that it is still installed. Monitoring identifies if a user or an attacker uninstalls the patch. It also identifies software restored to an unpatched version or factory-default state. Monitoring deployed patches also helps identify if behavior changes after patching. This may detect situations where the installed patch was itself compromised.

Patching vulnerabilities establishes evidence for the following CMMC Level 1 objectives:

- SI.L1-b.1.xii (f) - correct system flaws within the specified time frame

Evidence:

- List of recent security flaw remediation actions performed on the system

- List of installed patches, service packs, hotfixes, and other software updates

- Installation/change control records for security-relevant software and firmware updates

Policy Statement:

Vulnerability scanning

- We deploy vendor-supplied security patches within six months of their release. We deploy critical patches within two weeks of their release.

Run change advisory board meeting

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-41. Manage changes to firewall policies as part of a formal configuration management process. Many firewall interfaces audit changes but this does not always track policy changes. You should keep a log of all policy changes associated with the firewall. Consider attaching the log to the device or keeping it in the same part of the inventory system as the firewall. Some firewalls permit maintaining comments for each rule. When workable, document rulesets with comments on each rule. Most firewalls allow restrictions on who can make changes to the ruleset. Some allow restrictions on the addresses from which administrators can make such changes. Use such restrictions when possible.

This guidance originates from the discussion of CM-3 within NIST SP 800-53. Change control involves the proposal, justification, implementation, testing, review, and disposition of changes. This includes system upgrades, modifications, and vulnerability remediations. Change control covers changes to baselines as well as operational procedures. Configuration Control Boards or Change Advisory Boards review and approve proposed changes. For new systems or major upgrades, include development team representatives on the Board. Audit activities before, after, and associated with implementing system or component changes.

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-128. A well-defined change control process is fundamental to any security-focused configuration management program. Change control ensures an evaluation process is in place for requested configuration changes. You should assess the security impact and test the effectiveness before authorizing changes. The process may have different levels of rigor depending on risk tolerance. Configuration change control generally consists of the following steps:

- Requesting a change. A request for change may originate from the end user, a help desk, or from management. Changes may also originate from vendors, application updates, security alerts, or system scans. NIST SP 800-128 provides a Change Request Template.

- Recording the request for the proposed change. Define procedures to enter change requests into the configuration change control process. You may use paper-based methods, emails, a help desk, or automated tools to receive requests. Define procedures to track and route requests and allow for electronic acknowledgements.

- Determine if the proposed change requires configuration control. You may exempt some requests from change control procedures. If the change is exempt or pre-approved, note this on the change request and allow the change to be made without further analysis or approval; however, system documentation may still require updating (e.g., the System Security Plan, the baseline configuration, system component inventory, etc.).

- Analyzing the proposed change for its security impact on the system.

- Testing the proposed change for security and functional impacts. Testing confirms the impacts identified during analysis and/or reveals potential impacts. Present the impacts of the change to the Change Control Board (CCB).

- Approving the change. This step is usually performed by the CCB. The CCB may request adding controls if the change is necessary but has a negative impact on security. Coordinate implementation of new controls with the authorizing official and system owner.

- Implementing the approved change. Once approved, authorized staff makes the change. Depending upon the scope of the change, it may be helpful to develop an implementation plan. Change implementation includes changes to related configurations as well as updating system documentation. Notify stakeholders when the change requires a service interruption. Provide user and help desk training when the change alters system functionality.

- Verifying correct change implementation. This involves conducting vulnerability scans, or reassessing affected security controls. Implementation of changes can cause security issues. You should confirm the deployed change has no issues.

- Close out the change request. Define procedures to close out requests after completing the steps above.

Documenting configuration changes helps establish evidence for the following CMMC Level 1 practices:

- SI.L1-b.1.x (a) - defining the external system boundary

- SI.L1-b.1.x (b) - defining key internal system boundaries

- SI.L1-b.1.x (g) - protect communications at the external system boundary

- SI.L1-b.1.x (h) - protect communications at key internal boundaries

- SI.L1-b.1.xi (a) - identify system components accessible to the public

- SI.L1-b.1.xi (b) - separate system components accessible to the public from internal networks

Evidence:

- system design documentation

- enterprise security architecture documentation

- configuration settings and associated documentation

Policy Statement:

Configuration Management

- We review proposed changes to the system monthly. The change management review assesses the impact of all proposed system changes.

Review Website Content

This guidance originates from DCSA CUI FAQ. Federal Contract Information (FCI) is information not intended for public release. Contractors may receive FCI from the Federal Government under a contract. Contractors may also generate FCI as part of their participation in government contracts. Controlled unclassified information (CUI) and FCI share similarities and a particularly important distinction. Both CUI and FCI include information created or collected by or for the Government. Both also include as well as information received from the Government. CUI requires safeguarding and may be subject to dissemination controls. In short, all CUI in possession of a Government contractor is FCI, but not all FCI is CUI.

This guidance originates from control AC-22 within NIST SP 800-53. The public is not authorized to have access to nonpublic information. This includes information protected under the PRIVACT and proprietary information. This addresses systems controlled by the organization and accessible without identification or authentication. You should cover posting information on non-organizational systems by organizational policy. This control addresses the management of the individuals who make information accessible. Control AC-22 from has a FedRAMP Moderate assigned parameter that states:

- Review systems accessible to the public for nonpublic information at least quarterly. Remove such information, if discovered.

Reviewing systems accessible to the public establishes evidence for the following objectives:

- AC.L1-b.1.iv (d) review content on systems accessible to the public to ensure that it does not include FCI

- AC.L1-b.1.iv (e) put mechanisms in place to remove and address improper posting of FCI

Evidence:

- review records of information on systems accessible to the public

- records of response to nonpublic information on public websites

Policy Statement:

Access Control

- Only authorized individuals can post content to websites and social media. We train authorized individuals to identify non-public information. We review new content drafted for publication for nonpublic information. We conduct quarterly reviews of published content for nonpublic information. Authorized personnel remove nonpublic information discovered during these reviews.

Review Firewall Ruleset

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-41. Be aware that firewall rulesets can become complicated with age. A new firewall rule might address outbound user traffic and inbound email traffic. It will likely contain more rules by the time the firewall system reaches the end of its first year. It is important to review the firewall policy often. Such a review can uncover rules no longer needed. Reviews can also identify the need for new policy requirements.

It is best to review the firewall policy at regular intervals. You should not wait to do reviews during audits or emergencies. Reviews should include an examination of all changes since the last regular review. You should review who made the changes and under what circumstances. It is also useful to have people not part of the policy review team perform ruleset audits. This provides an outside view of how the policy matches the organization’s goals. Some firewalls have tools that can do automated reviews of policies. These tools help find redundant rules or missing recommended rules. Use such tools at regular intervals as part of the regular policy review.

Reviewing firewall policies creates evidence for the following CMMC Level 1 objectives:

- SC.L1-b.1.x (e) control communications at the external system boundary

- SC.L1-b.1.x (f) control communications at key internal boundaries

- SC.L1-b.1.xi (b) separate system components accessible to the public from internal networks.

Evidence:

- security architecture documentation

- system configuration settings and associated documentation

- enterprise security architecture documentation

Policy Statements:

System and Communication Protection

- We maintain a firewall to block all traffic not permitted by policy.

- We protect web servers and VPN gateways within a demilitarized zone (DMZ).

- Remote and wireless connections must use a VPN to access internal systems.

Maintain Physical Access Authorizations

While AC-2 focuses on system access, PE-2 focuses on facility access. Control PE-2 has a FedRAMP Moderate assigned parameter that states:

- Review the access list detailing authorized facility access by individuals once a year.

Maintaining an authorized account list helps meet the following CMMC Level 1 objectives:

- PE.L1-b.1.viii (a) - limit physical access to environments to authorized individuals

Evidence:

- authorized personnel access list

- physical access list reviews

- physical access termination records and associated documentation

Policy Statement:

Access Control

- We document all authorized user credentialing activities. We maintain accurate records of authorized users from on-boarding to termination. Job requirements are the basis for access to systems, data, and non-public spaces.

Review of Account Types

This guidance originates from control AC-2 within NIST SP 800-53. System account types may include individual, system, developer, and service. Users with administrative privileges should receive more scrutiny for approval. Organizations may prohibit shared, group, emergency, anonymous, temporary, and guest accounts.

You may define access privileges by account, type of account, or a combination of the two. Other attributes required may include restrictions on time, day, and point of origin. Consider related business requirements when defining other access privilege attributes. Failure to consider these factors could affect system availability.

Restrict temporary and emergency accounts for short-term use. You may establish temporary accounts without the need for immediate account activation. You may establish emergency accounts out of the need for rapid account activation. Emergency account activation may bypass normal account authorization processes. Do not confuse emergency and temporary accounts with accounts used less often. This includes local logon accounts used for special tasks. Keep such accounts available and do not subject them to automatic disabling. Conditions for disabling or deactivating accounts include when they are no longer required. Conditions for disabling also include transferred or terminated individuals. Change shared/group authenticators when members leave the group. This ensures that former group members do not keep access to the shared or group account. Some types of system accounts may need specialized training.

Documenting this review establishes evidence for the following CMMC Level 1 objectives:

- AC.L1-b.1.ii (a) define the types of transactions and functions that authorized users can execute.

Evidence:

- list of approved authorizations including remote access authorizations

- system configuration settings and associated documentation

Policy Statement:

Access Control

- We document all authorized user credentialing activities. We maintain accurate records of authorized users from on-boarding to termination. Job requirements are the basis for access to systems, data, and non-public spaces.

- Role-based access controls restrict access to systems, data, and functions.

Update Network Diagram

A network diagram shows a perspective of the network, not the whole network. Network diagrams may show connections, layers of access, network routing, or data flow. Network diagrams should address and depict components reflected in the authorization boundary, and:

- Subnetting

- Location of DNS servers

Organizations should update the network diagram at least once per year. Adding or removing system components should prompt more frequent updates.

Updating the network diagram establishes evidence for the following CMMC Level 1 objectives:

- AC.L1-b.1.iii (a) identify connections to external systems

- AC.L1-b.1.iii (e) control/limit connections to external systems

- SC.L1-b.1.x (a) define the external system boundary

- SC.L1-b.1.x (b) define key internal system boundaries

- SC.L1-b.1.xi (a) identify system components accessible to the public

- SC.L1-b.1.xi (b) separate system components accessible to the public from internal networks.

Evidence:

- system design documentation

- system configuration settings and associated documentation

- list of applications accessible from external systems

- list of key internal boundaries of the system

- boundary protection hardware and software

- enterprise security architecture documentation

Policy Statement:

System and Communication Protection

- We maintain a firewall to block all traffic not permitted by policy.

- We protect web servers and VPN gateways within a demilitarized zone (DMZ).

- Remote and wireless connections must use a VPN to access internal systems.

Conduct annual risk assessment

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-47. An interconnection is a direct connection between two or more systems. These systems operate in different authorization boundaries. Interconnections may exchange information and/or allow access to information, services, and resources. Base the decision to allow interconnections on an assessment of associated risks.

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-41. Perform a risk analysis before creating a firewall policy. Develop a list of the types of traffic needed by the organization and categorize how to secure them. Identify the types of traffic that can traverse a firewall under what circumstances. Base the risk analysis on threats; vulnerabilities; countermeasures; and compromise impact.

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-30. Conducting risk assessments includes the following specific tasks:

- Identify threat sources that are relevant to organizations;

- Identify threat events those sources could produce;

- Identify exploitable vulnerabilities by threat sources through specific threat events

- Identify predisposing conditions that could affect successful exploitation;

- Determine the likelihood that threat sources would attempt specific threat events

- Determine the likelihood that the threat events would be successful;

- Determine the adverse impacts to operations and assets

- Determine information security risks as a combination of likelihood and impact

- Include any uncertainties associated with the risk determinations.

Conducting a risk assessment on interconnections to establishes evidence for the following objectives:

- AC.L1-b.1.iii (e) control/limit connections to external systems

Evidence:

- list of applications accessible from external systems

- system configuration settings and associated documentation

- risk assessment results, reviews, and updates

Policy Statement:

Risk Assessment

- We conduct a risk assessment before authorizing any connections to external systems. The risk assessment determines the inherent and mitigated risk of enabling any connection.

Provide cybersecurity awareness training

This guidance originates from control AC-20 within NIST SP 800-53. Authorized individuals include anyone with authorized access to organizational systems. Organizations are able to impose specific rules of behavior related to system access. Restrictions that organizations impose on authorized individuals need not be uniform. The restrictions may vary depending on trust relationships between organizations.

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-83. Implementing awareness programs can provide guidance to users on malware incident prevention. You should make all users aware of the ways that malware enters and infects hosts. Discuss the risks of malware and the importance of users in preventing incidents. Emphasize best practices to avoid social engineering attacks. Make users aware of policies and procedures that apply to malware incident handling. Identify how to report a suspected incident and what users might need to do. Malware awareness programs reduce incidents that occur through human error.

Providing malware awareness and external system usage training establishes evidence for:

- AC.L1-b.1.iii (f) controlling/limiting the use of external systems

- AC.L1-b.1.xiii (b) providing protection from malicious code at designated locations

Evidence:

- procedures addressing the use of external systems

- record of actions initiated by malicious code protection mechanisms in response to detection

Policy Statement:

Awareness and Training

- We train all employees on how to safeguard sensitive information. This training focuses on identifying threats and protecting organizational systems and information.

Role-Based Training

There are three roles with specific CMMC Level 1 training requirements:

- Individuals authorized to post content on public systems

- Individuals with assigned sanitization responsibilities

- Members of the IT team that handle malware incidents

Training individuals authorized to post content on systems accessible to the public

NIST made this training explicit within SP 800-171 Rev 3. Train individuals posting content on systems accessible to the public. This training should cover how to identify nonpublic information. Extend this training to include Controlled Unclassified Information when seeking CMMC Level 2.

The US Government does not provide training related to Federal Contract Information (FCI). We created one and posted it for anyone to use on YouTube.

We cover the definition of FCI and the requirements around controlling public information. The training provides several examples to train staff on identifying FCI. The Department of Defense publishes training on Controlled Unclassified Information. Consider using this free training for individuals posting content on your website. a

Providing training on identifying nonpublic information establishes evidence for the following objectives:

- AC.L1-b.1.iv (b) identify procedures to ensure FCI is not posted or processed on systems accessible to the public;

Evidence:

- training materials and/or records

Policy Statement:

Awareness and Training

- We train individuals posting content to the organization's website to identify nonpublic information.

Training individuals with assigned sanitization responsibilities

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-88. A key element of verifying sanitization is the training and expertise of personnel. Organizations should ensure that equipment operators are competent to perform sanitization functions. We created a training video that reviews processes derived from NIST SP 800-88:

- Determining Types of Media in Use

- Security Categorizations

- Disposition Decision Flowchart

- Verification

- Device Markings

- Documentation

Providing training to staff assigned media sanitization responsibilities establishes evidence for the following:

- MP.L1-b.1.vii (a) sanitize or destroy system media containing FCI before disposal

- MP.L1-b.1.vii (b) sanitize system media containing FCI before reuse

Evidence:

- applicable standards and policies addressing media sanitization

Policy Statement:

Awareness and Training

- Individuals with assigned sanitization responsibilities for digital media complete annual training. This training covers the latest techniques and best practices for data sanitization.

Training members of the IT team that handle malware incidents

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-83. The initial phase of malware incident response involves performing preparatory activities. This includes developing malware incident handling procedures and training for incident response teams. Identify staff who might need to assist during malware incidents in advance. Provide staff with documentation and periodic training on their possible duties. Conduct awareness activities for staff involved and provide training on specific tasks.

Training staff with malware incident response responsibilities establishes evidence for the following:

- SI.L1-b.1.xiii (b) provide protection from malicious code at designated locations

Evidence:

- procedures addressing malicious code protection

Policy Statement:

Awareness and Training

- All members of the IT team take annual training on malware prevention. This training covers how malware infects hosts and spreads.

Review log event types

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-61 Rev 2. An event is an observable occurrence in a system or network. Hosts should have auditing enabled and should log significant security-related events.

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-92. Logs created within an organization could have some relevance to computer security. For example, logs from network devices might record data that could be of use. These logs are generally used as supplementary sources for computer security. Consider the value of log data sources when implementing log management.

Security Software

Most organizations use several types of software to detect malicious activity. Security software is a major source of computer security log data. Common types of network-based and host-based security software include the following:

- Antimalware Software. TThe most common form of antimalware software is antivirus software. This may record instances of detected malware, disinfection attempts, and file quarantines. Antivirus software might also record malware scan results and software updates. Antispyware and other types of antimalware are also common sources of security information.

- Intrusion Detection and Intrusion Prevention Systems. Intrusion Detection and Intrusion Prevention Systems. Intrusion detection and prevention systems record information on suspicious behavior and detected attacks. They may also record actions performed to stop malicious activity in progress.

- Remote Access Software. Remote access is often granted and secured through virtual private networking (VPN). VPN systems may record login attempts and times each user connected and disconnected. They may also record the amount of data sent and received in each user session. VPN systems that support granular access control may log information about resource use.

- Web Proxies. Web proxies are intermediate hosts through which users access Web sites. Web proxies make Web page requests on behalf of users. They cache copies of retrieved Web pages to make access to those pages more efficient. You can use Web proxies to restrict access and to add a layer of protection between Web clients and Web servers. Web proxies often keep a record of all URLs accessed through them.

- Vulnerability Management Software. Vulnerability management software includes patch management software and vulnerability assessment software. These systems record the patch installation history and vulnerability status of each host. These records identify known vulnerabilities and missing software updates. Vulnerability management software may also record information about hosts’ configurations.

- Authentication Servers. Authentication servers include directory servers and single sign-on servers. They may record authentication attempts, their origin, username, success or failure, and time.

- Routers. You may configure routers to permit or block certain types of network traffic based on a policy. Routers that block traffic may only record basic characteristics of blocked activity.

- Firewalls. Firewalls can permit or block activity based on a policy. Firewalls use more sophisticated methods to examine network traffic. Firewalls can also track the state of network traffic and perform content inspection. Firewalls tend to have more complex policies and generate detailed logs of activity.

- Network Quarantine Servers. Some organizations check each remote host’s security posture before allowing network access. This is often done through a network quarantine server and agents placed on each host. You may quarantine hosts on a separate virtual local area network that do not respond or fail the checks . These systems record the status of checks and the reasons for quarantining a host.

Operating Systems

Operating systems for servers, workstations, and networking devices record security-related information. The most common types of security-related OS data are as follows:

- System Events. System events are operational actions performed by OS components. This includes shutting down the system or starting a service. Operating systems record railed events and significant successful events. Many OSs permit administrators to select which types of events to record. The details recorded for each event may vary. Events are usually timestamped. Records may include status, error codes, service name, and user or system account.

- Audit Records. Audit records contain security event information. This includes authentication attempts and file access. Audit records may also capture policy or account changes and the use of privileges. OSs may permit system administrators to specify which types of events to record. You should log successful and/or failed attempts to perform certain actions.

Applications

Some applications generate their own log files. Other applications use the logging capabilities of the OS. Applications vary in the types of information that they log. The following lists some common logged types of information and their benefits:

- Client requests and server responses. These are helpful in reconstructing sequences of events and determining their outcome. If the application logs user authentications, it can help identify users making requests. Some applications can perform detailed logging. E-mail servers record the sender, recipients, subject name, and email attachments. Web servers record each URL requested and the type of response provided by the server. Business applications record financial records accessed by each user. You can use this information to identify or investigate incidents. It is also helpful for monitoring application usage for compliance and auditing purposes.

- Account information. This includes authentication attempts, account changes, and use of privileges. This is helpful in identifying brute force password guessing and escalation of privileges. It can also identify who has used the application and when each person has used it.

- Usage information. This includes the number of and size of transactions within a certain period of time. This can be useful for certain types of security monitoring. For example, increased email activity might identify a new email–borne malware threat. A large outbound email message might identify inappropriate releases of information.

- Significant operational actions. This includes application startup and shutdown, application failures, and major application configuration changes. This might identify security compromises and operational failures.

This guidance originates from AU-2 within NIST SP 800-53. The types of events to log are those events that are significant and relevant to system security. Event logging also supports specific monitoring and auditing needs. Event types include password changes and failed logons or failed accesses. Other event types include security attribute changes and administrative privilege usage. Data action changes, query parameters, or external credential usage are also important events. Consider the monitoring and auditing requirements when determining the event types to log. Event logging should include all protocols that are operational and supported.

Control AU-2 has a FedRAMP Moderate assigned parameter that states:

- Review and update the event types selected for logging at least once a year. Review and update logged event types when there is a change in the threat environment.

Identify a subset of event types to log. This will help balance monitoring and auditing requirements with other system needs. For example, you may want to log every file access that is successful and unsuccessful. You may select to log events occurring under specific circumstances. Reducing the quantity of logged events reduces the burden on system performance. The types of logged events may change. Reviewing and updating the types of events logged ensures the events remain relevant. Consider how the types of logging events can reveal information about individuals. Consider the privacy risk and identify how best to mitigate such risks.

You can generate audit records at various levels. For example, logging information at the packet level as information traverses the network. Recording the appropriate level of events can identify the root causes of problems. When defining event types, consider the logging necessary to cover related event types. This may include the process steps and actions that occur in service-oriented architectures.

Other requirements may identify the need to log specific event types . These events include:

AC-2(4) - Account creation, modification, enabling, disabling, and removal actions.

AC-3(10) - Overrides of automated access control mechanisms under defined conditions.

AC-6(9)- The execution of privileged functions in audit logs.

AC-17(1)- Connection activities of remote users on a variety of system components. This includes servers, notebook computers, workstations, smart phones, and tablets.

CM-3f - Activities associated with configuration-controlled changes to the system.

CM-5(1)- System accesses associated with applying configuration changes.

IA-3(3.b) - Lease information related to dynamic address allocation for devices.

MA-4(1) - Defined events for nonlocal maintenance and diagnostic sessions

MP-4(2) - Access attempts and granted access to media storage areas

PE-3 - Physical access audit logs for defined entry or exit points

PM-21 -Disclosures of personal information. This includes the date, nature, and purpose of each disclosure; and name and address.

PT-7 - Application of defined processing conditions or protections for personal information.

SC-7(9) - The identity of internal users associated with denied communications

SC-7(15) - Networked, privileged accesses

SI-3(8) - Unauthorized operating system commands for kernel functions that are suspicious.

SI-4(22) - Unauthorized or unapproved network services

SI-7(8) - Software, firmware, and information integrity violations

SI-10(1) - Manual overrides for input validation

Reviewing logged event types establishes evidence for the following CMMC Level 1 objectives:

PE.L1-b.1.ix (c) maintain audit logs of physical access;

SC.L1-b.1.x (g) protect communications at the external system boundary; and

SC.L1-b.1.x (h) protect communications at key internal boundaries.

SI.L1-b.1.xiii (b) provide protection from malicious code at designated locations

Evidence:

- system audit logs and records

- physical access control logs or records

Policy Statement:

Audit and Accountability

- We review logged event types on an annual basis. Reviews and updates may also occur in response to changes in the threat environment. .

Test boundary protection devices

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-41 Rev 1. Consider conducting penetration testing to assess the security of your network environment. Testing can verify firewall performance by comparing network traffic with its expected response. Consider employing penetration testing as a complement to a conventional audit program.

Testing boundary protection devices establishes evidence for the following CMMC Level 1 objectives:

SC.L1-b.1.x (e) control communications at the external system boundary; and

SC.L1-b.1.x (f) control communications at key internal boundaries.

SC.L1-b.1.xi (b) separate system components accessible to the public from internal networks

Evidence:

- boundary protection hardware and software

- enterprise security architecture documentation

Policy Statements:

System and Communications Protection

- We maintain a firewall to block all traffic not permitted by policy.

Review and update policies and plans

As set forth in 32 CFR § 170.24, documents need to be in their final forms. Drafts of policies or documentation are not eligible because they are not official.

Policies

This guidance originates from the CMMC Level 1 Assessment Guide for AC.L1-B.1.III. Establish terms for the use of external systems using policies and procedures. This guidance originates from SI.L1-B.1.XII. Software vendors release patches, service packs, and hot fixes. Make sure your software that processes FCI is up to date. Develop a policy that requires checking vendor websites for flaw notifications every week. The policy states you patch computers weekly, and servers monthly.

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-83 Rev1. Policy statements are the basis for malware prevention efforts. This includes user and staff awareness, vulnerability mitigation, threat mitigation, and defensive architecture. Malware prevention–related policy should be as general as possible. This provides flexibility in implementation and reduces the need for frequent policy updates. It should also be specific enough to make the intent and scope of the policy clear. Malware prevention–related policy should include provisions related to remote workers. Policies should address using hosts within and outside organizational control. Organizations should have policies and procedures to mitigate vulnerabilities that malware might exploit.

Updating policies establishes evidence for the following CMMC Level 1 objectives:

AC.L1-b.1.iii (f) control/limit the use of external systems

SI.L1-b.1.xii (a) specify the time within which to identify system flaws

SI.L1-b.1.xii (c) specify the time within which to report system flaws

SI.L1-b.1.xii (e) specify the time within which to correct system flaws

SI.L1-b.1.xiii (b) provide protection from malicious code at designated locations

Evidence:

- Policy, process, and procedure documents

Policy Statements:

Security Assessment

- The CIO will update and review this policy every year. Security incidents or changes in organizational structure or regulatory requirements may prompt updates.

Plans

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-40 Rev 4. Define a maintenance plan for each maintenance group and applicable risk response scenario. A maintenance plan defines actions taken when a scenario occurs. This includes the timeframes for beginning and ending each action.

This guidance originates from NIST SP 800-61 Rev2. Have a formal incident response plan for implementing the incident response capability. The plan should lay out the necessary resources and management support. The incident response plan should include the following elements:

- Mission, strategies and goals

- Senior management approval

- Organizational approach to incident response

- Communication with the rest of the organization and with other organizations

- Metrics for measuring the incident response capability and its effectiveness

- Roadmap for maturing the incident response capability

- How the program fits into the organization

Discuss the incident response program structure within the plan. Develop a plan and gain management approval. Review it at least once a year. This will help ensure the organization is maturing the capability.

Updating plans establishes evidence for the following CMMC Level 1 objectives:

SI.L1-B.1XII(d) report system flaws within the specified time frame

SI.L1-B.1.XIII(b) provide protection from malicious code at designated locations

Evidence:

- Plans and planning documents

Policy Statements:

Maintenance

- We define maintenance groups to identify outage restrictions, impact levels, and existing mitigations.

Incident Response

- We maintain an incident response capability by testing the incident response plan.

Conclusion

We defined these tasks to gauge the efficacy of basic security requirements. These 18 tasks only satisfy 8 of the 56 CMMC Level 1 requirements. This plan aligns continuous monitoring activities for another 29 objectives. This plan should complement hardware and software configurations, policies and procedures. By implementing an ISCM program, you establish a stronger foundation for CMMC Level 2.

Emphasize your product's unique features or benefits to differentiate it from competitors

In nec dictum adipiscing pharetra enim etiam scelerisque dolor purus ipsum egestas cursus vulputate arcu egestas ut eu sed mollis consectetur mattis pharetra curabitur et maecenas in mattis fames consectetur ipsum quis risus mauris aliquam ornare nisl purus at ipsum nulla accumsan consectetur vestibulum suspendisse aliquam condimentum scelerisque lacinia pellentesque vestibulum condimentum turpis ligula pharetra dictum sapien facilisis sapien at sagittis et cursus congue.

- Pharetra curabitur et maecenas in mattis fames consectetur ipsum quis risus.

- Justo urna nisi auctor consequat consectetur dolor lectus blandit.

- Eget egestas volutpat lacinia vestibulum vitae mattis hendrerit.

- Ornare elit odio tellus orci bibendum dictum id sem congue enim amet diam.

Incorporate statistics or specific numbers to highlight the effectiveness or popularity of your offering

Convallis pellentesque ullamcorper sapien sed tristique fermentum proin amet quam tincidunt feugiat vitae neque quisque odio ut pellentesque ac mauris eget lectus. Pretium arcu turpis lacus sapien sit at eu sapien duis magna nunc nibh nam non ut nibh ultrices ultrices elementum egestas enim nisl sed cursus pellentesque sit dignissim enim euismod sit et convallis sed pelis viverra quam at nisl sit pharetra enim nisl nec vestibulum posuere in volutpat sed blandit neque risus.

Use time-sensitive language to encourage immediate action, such as "Limited Time Offer

Feugiat vitae neque quisque odio ut pellentesque ac mauris eget lectus. Pretium arcu turpis lacus sapien sit at eu sapien duis magna nunc nibh nam non ut nibh ultrices ultrices elementum egestas enim nisl sed cursus pellentesque sit dignissim enim euismod sit et convallis sed pelis viverra quam at nisl sit pharetra enim nisl nec vestibulum posuere in volutpat sed blandit neque risus.

- Pharetra curabitur et maecenas in mattis fames consectetur ipsum quis risus.

- Justo urna nisi auctor consequat consectetur dolor lectus blandit.

- Eget egestas volutpat lacinia vestibulum vitae mattis hendrerit.

- Ornare elit odio tellus orci bibendum dictum id sem congue enim amet diam.

Address customer pain points directly by showing how your product solves their problems

Feugiat vitae neque quisque odio ut pellentesque ac mauris eget lectus. Pretium arcu turpis lacus sapien sit at eu sapien duis magna nunc nibh nam non ut nibh ultrices ultrices elementum egestas enim nisl sed cursus pellentesque sit dignissim enim euismod sit et convallis sed pelis viverra quam at nisl sit pharetra enim nisl nec vestibulum posuere in volutpat sed blandit neque risus.

Vel etiam vel amet aenean eget in habitasse nunc duis tellus sem turpis risus aliquam ac volutpat tellus eu faucibus ullamcorper.

Tailor titles to your ideal customer segment using phrases like "Designed for Busy Professionals

Sed pretium id nibh id sit felis vitae volutpat volutpat adipiscing at sodales neque lectus mi phasellus commodo at elit suspendisse ornare faucibus lectus purus viverra in nec aliquet commodo et sed sed nisi tempor mi pellentesque arcu viverra pretium duis enim vulputate dignissim etiam ultrices vitae neque urna proin nibh diam turpis augue lacus.

![[ANSWERED] Who is Responsible for Protecting CUI?](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/67e2b8210878abcba6f91ae6/68ad0fdb15f797aa9be2e37a_WhoisResponsibleforProtectingCUI_324.avif)